Photo: Nguyen Thanh Tung

Vietnam Heritage, June-July 2011 — The land just above Mui Ne beach, near Phan Thiet, had been taken over by ‘resorts’. Next in proximity to the beach ran Nguyen Dinh Chieu Street, then, on the far side of it, restaurants, grocery stores, coffee bars, souvenir shops, travel agencies and a few small restaurants.

From the street, I could not see the sea, or what looked like a public beach. I felt I was being asked to think about staying at a resort with the works, swimming pools, spa salons, hair salons and a restaurant with a continental breakfast. The prices at the resorts ranged from $US50 to $US200.

At Mui Ne [Mũi Né, in Vietnamese], sand is everywhere. You can find it in your camera. At the back edges of the beaches, they grow sheoak hedges and trees to protect themselves from sand borne on the prevailing wind. When you ride a bike, the wind makes you weave.

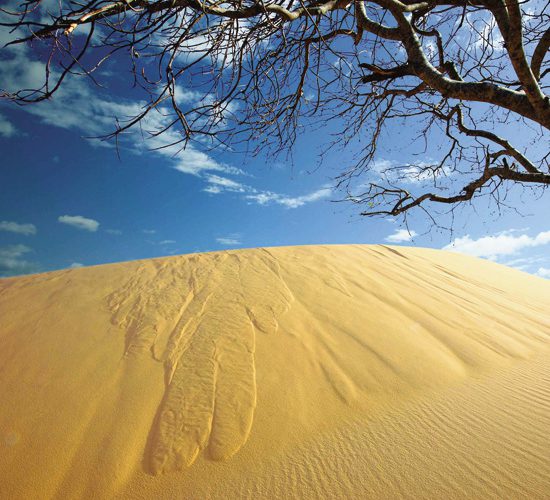

Huge sand dunes further back from Mui Ne beach, ‘resorts’ and shops are called flying dunes; the wind changes their shape every hour.

Mui Ne sand is red in an area of ancient iron ore, white around the border between Ninh Thuan and Binh Thuan Provinces, black and red in Bong Lai Tien Canh and yellow and brown on a certain part of the beach. Mui Ne sand has 18 tones.

To explore the 18 tones, Jeeps are available. It costs about VND400,000 ($20) for a trip in an open machine to Suoi Tien (Fairy Spring), Con Cat Do (Red Sand Island) and Con Cat Trang (White Sand Island). [Cồn: island, cát: sand, Ä‘á»: red, trắng: white. These ‘islands’ are not islands in the sense of being completely surrounded by water.] Hot air coming from the sand dunes blew my hair into a whirlwind during 30 kilometres in the hands of a Phan Thiet driver.

Suoi Tien is in Nguyen Dinh Chieu Street. We found a brook in a state of neglect with a chain of stalaciform hillocks of sand hardened to stone by wind. Clear water flowed over a bed of fine, rosy sand.

A red sand dune was to be found a few kilometres from the centre of the ‘resort’ area.

Vast white sand dunes appeared 20 kilometres away, beside a lake of lotus flowers on the side of which was a sparse forest of sheoaks. Prize-winning photographs had been taken here.

While Mui Ne waters are used for windsurfing [There are international competitions], its sand dunes are used for sand-surfing. Children stood at a parking space ready to rent out boards for VND20,000 ($1). Children on horseback galloped up to us and asked if we wanted to hire a horse. None of the people who carried boards could surf, but you could hire a ‘guide’. It was hard to slide even a few metres, though the dune was immense.

I complained to the owner of the sand-surfboard business that I hadn’t done any surfing. A boy standing nearby said, ‘You can’t do the surfing without hiring a “guideâ€.’

I stayed at the resort two more days. It was a short walk to the beach. You could lie on a bench and look at the moon and sky through sheoaks. You could kindle a small fire. I ate sweet-smelling oyster soup and one-day-dried squid, a local specialty.

Late in the afternoon, the shops were crowded with tourists.

The souvenirs included ‘pearls’ so cheap one might have thought they were not real. They were mostly of irregular shape, with many flaws. Along the street were baskets of pearls, white, black and other colours. Pearls were plaited into strings, long, short, big, small, single, double, in earrings, fingerrings and necklaces. The prices went as low as a few dozen thousands of dongs, for a ring. There were hundreds of pearl shops.

I moved to the Ke Ga Lighthouse resort, about 30 kilometres south of the Phan Thiet post office [whereas Mui Ne is a short drive from and on the other side of Phan Thiet]. This ‘resort’ was in a quieter place, though the ‘resorts’ occupied every metre along the beach. The Hana Beach Resort is pretty large, with high-quality bungalows, and there is, in more space, the high-class Princess d’Annam. The lighthouse itself, more than 100 years old, we got to in a coracle.

I rented a motorbike from a watchman of the Hana Beach Resort to go to the 400-metre-high Ta Cu Mountain, near Thuan Nam Town, Ham Thuan Nam District, Binh Thuan Province.

On the way I saw the orchards of thanh long, dragon fruit, which were lit up with electric light when the sun went down. The thanh long trees are favoured by this area of sand, wind and light. The thanh long tree is not pretty, a kind of cactus that bears not-so-pretty fruit, the taste of which is so good many Californian Vietnamese grow them there.

There were also fields of salt, and workers harvesting it in wheelbarrows.

I reached Ta Cu Mountain at 5 p.m., wanting to visit the Sakyamuni Buddha entering Paranirvana, which is 49 metres long and 4 metres high, in concrete on a steel skeleton, built in 1963, close to the mountain-top. There is a cable car, but I heard an operator say, ‘Can you come back tomorrow?’ Alternatively, I could stay overnight on the mountain, including a vegetarian meal.

A big group of tourists arrived, however, and the-cable-car-operators agreed to postpone closing time by an hour. I would see the statue before sunset.