(No.5, Vol.3, June 2013 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

Researcher Van Tan maintains that the first totem of the ancient Vietnamese was the snake, which later became

the dragon, but along the way, it may have become the crocodile. He writes, ‘In the age of Hung Kings [founders of Vietnam, who are believed to have existed between 3000 BC and 200 BC], the Vietnamese tattooed themselves with images of the giao long or serpentine leviathan, but by the Tran Dynasty, they tattooed themselves with images of the dragon.’

Many Chinese histories record that people of the Dong Son [a culture that existed from 700 to 100 BC] had a custom of tattooing themselves with pictures of the giao long-the serpentine leviathans beneath the water. The giao long may have been the thu?ng lu?ng sea serpent, or it could also have been the crocodile, which are both vicious beasts that frequently harmed riverine inhabitants.

Crocodile patterns decorate the bronze artefacts at historical sites associated with the Dong Son culture. These are the crocodiles on the Dao Thinh bronze jar, Ninh Binh belt buckle, four bronze axes, three bronze spears, and one bronze dagger collected by the Museum of Fine Arts from Dong Son historical sites scattered throughout Thanh Hoa.

Legend holds that in the year 1282, a crocodile entered the Phu Luong River (now the Red River), and Nguyen Thuyen was ordered by the court to erect a sacrificial altar and compose a prosodic eulogy in the Nôm demonic script, which was cast into the river, dispelling the crocodile.

The crocodiles of the lands of the South were described by Trinh Hoai Duc in the Gia ??nh thành thông chí (Comprehensive Gazetteer of Gia Dinh City), possibly the oldest source that recounts crocodiles in the South. The gazetteer says that crocodiles had rectangular heads, furrowed eyebrows, split tails, serrated grooves, and jagged canines and that they lacked ear lobes, had four legs, were without scales, and had powerful tails. There was a kind of yellow and black crocodile that was as big as a canoe and especially ferocious. People who went out on the river by boat were often tossed into the river by the thrashing of a crocodile’s tail and then dragged out in its teeth to the riverbank to be eaten.

During two months in 1880, the people of Co Co (Soc Trang Province) caught 189 crocodiles to receive a reward and extirpate the threat.**

Elder Tran Van Tot, who is 86 years old and hails from a family that has lived as open water stilt-net fishermen for many generations in the Dau Sau Rivulet Mouth in Tien Giang Province, relates, ‘My grandfather and father told their children that “Around the start of the 20th century, there was a Cham tribe of famous crocodile hunters that would seek out and kill crocodiles as big as a canoe-six meters long!”’

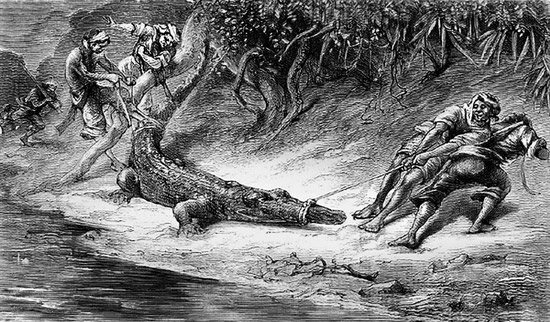

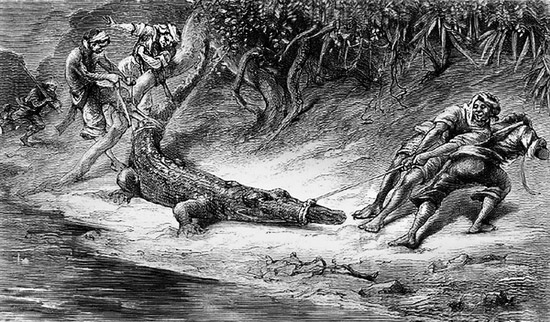

As for ferocious saltwater crocodiles, a popular method of catching them is to use a duck or dog as bait. The bait is hooked to a large, sharp fishhook and fastened with a sturdy, long fishing line. The hunter holds the bait and wades in the water to lure the crocodile. When the crocodile opens its mouth intending to bite, the fisherman deftly throws the bait into its mouth. The crocodile gets caught on the hook and writhes violently. Once the crocodile is exhausted, people pull the crocodile onto the riverbank.

Another method of hunting crocodiles is quite unique; it does not require the use of bait and is very risky. The hunter stands in the river, holding a fishhook in his hands. When a crocodile catches the hunter’s scent and approaches, opening its mouth to bite, the hunter quickly throws the fishhook into the crocodile’s mouth. Only dauntless and experienced individuals dare to carry out this hunting method.

The people of the U Minh Ha region deep in the Mekong Delta initiated the setting of fire to catch crocodiles that live in ponds within the forest.

In the novel ??t r?ng ph??ng Nam (Forest Lands of the South), writer Doan Gioi dedicates an entire chapter to the heading ‘The Craft of Crocodile Hunting,’ in which he narrates crocodile hunting in the past. Hunters set plants to hang and dry in the sun for several days until they were dry. Then they dug a small ditch from a pond, where crocodiles came out into the forest, so that the further it extended from the pond the more shallow it gradually became over a length of 10 metres. After that, they tossed the dried trees and grasses so that they tightly covered the surface of the pond and then set it on fire.

Once the fire burned out, the surface of the pond was discreetly covered beneath a layer of ash two or three finger knuckles thick. When the crocodiles surfaced to breathe, the ash burned their eyes and, if they stayed submerged too long, they ran out of breath, so they had to run onto the riverbank. Following after the tails of one another, they crawled along the ditch. When they spotted people, each crocodile opened its jaws, intending to bite. The hunters then immediately stuffed chunks of wood down their throats. When the crocodiles chomped on the wood, their two jaws got stuck and they could not open them. The hunters instantly grabbed the machetes tucked behind their backs and severed the tendons of the crocodiles’ tails. At that point, the crocodiles’ tails lost their function. The hunters used bamboo twine to tie their two rear legs above their backs, while the two front legs were left alone. Their jaws were clamped shut. Each pond could yield a catch of several dozen crocodiles in one day.

Crocodile was an unusual dish for middle-stream people in former days. During death anniversaries, one or two crocodiles were always butchered as a dish more luxurious than pork. The tail of the crocodile was most detectible. It was boiled, dipped in anchovy fish sauce, and eaten with acrid bananas. Chinese in Vietnam did not eat crocodile meat, since they feared revenge when they returned home by boat.

Crocodile meat is white, dry, and fibrous like stingray meat. It is crisp and aromatic with a fish or chicken flavor. Before 1945, crocodile rafts often transported hundreds of crocodiles to the markets of My Tho and Can Tho in the Mekong Delta.

The Vietnamese regard the crocodile as an incarnation of the river god.

In Vinh Phuoc B Commune, Go Quao District, Kien Giang Province in the Mekong Delta, there is a shrine for the worship of the Crocodile God. The people in the region venerate him as the River God.

Catching crocodiles in the Mekong Delta

Photo: From the archive of Bui Vy Van

In the task of taming new lands, inhabitants of the Mekong Delta had to face the powers of nature. Among them were ferocious kinds of crocodile, which are particularly vividly reflected in folk songs, stories and legends.

The crocodiles’ mark is evident in multifarious place names in the Mekong Delta:

In Cai Lay, Tien Giang Province is ?ìa S?u (Crocodile Pond).

R?ch ??u S?u (Crocodile Head Canal) in Vinh Dai Commune, Vinh Hung District, Long An Province.

?p ??u S?u ?ông (East Crocodile Head Hamlet) and ?p ??u S?u Tây (West Crocodile Head Hamlet), Loc Ninh Commune, Hong Dan District, Bac Lieu Province.

??u S?u (Crocodile Head) Bridge in Cai Rang District of Can Tho City is a ‘Crocodile Head’ because the ancient Vietnamese were afraid of crocodiles, so they often worshiped crocodile heads along the river (according to Son Nam). Around 1940, scenes of preparing crocodile meat still existed in this area. In An Bình Ward, Can Tho City, there is still an ancient Buddhist pagoda that bears the name ‘Chùa Ông Vàm ??u S?u’ or ‘Pagoda of the Gentleman of Crocodile Head Rivulet Mouth.’

* Mr Nguyen Thanh Loi teaches culture at The National College of Education Ho Chi Minh City

** From the book Nh?ng trang ghi chép v? l?ch s? v?n hóa Ti?n Giang, by Nguyen Phuc Nghiep, Tre Publishing House, 1998.