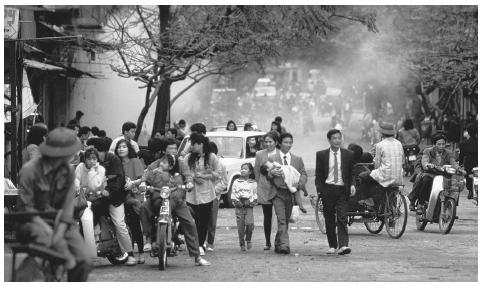

Vietnam Heritage, February 2011 — As an American, I remember that night as the dark of the moon; if I were Vietnamese, I would call it the fourth night of Tết in the Year of the Snake, 1989, before Hanoi became the city we know today: before the influx of westerners and western capital; before the hotels and restaurants and shops and stalls; before you could telephone reliably across town; before neon lights, before traffic lights, before street lights; before motorcycles, before taxis, before cars. Hanoi was a quiet town then, before it became a city.

I had spent the first days of Tết that year with a family in rural Ninh Binh Province.

At the time, I was the only foreigner allowed to stay with an ordinary family in the countryside. It had taken me years to secure the permission for such visits, which an international guest can now organise in a few days. Yet even though I’d stayed with rural families, I had yet to visit the homes of Hanoi friends.

By the fourth night of Tết, I was back in Hanoi in the cheapest room at the back of the third floor of the Thong Nhat (Unification) Hotel, now the Sofitel Métropole. The Unification had a few permanent residents but no guests except for me and the rats. I stayed amidst remnants of French colonialism – a filigree metal soap dish in the bathroom, a high bed, and a single ornate lamp shade in the high French ceiling.

In those days, the Hoa Binh Dam was not yet fully operational. My room’s single overhead bulb provided only enough light to move around. However, I could read if I was brave enough to stick the plugless copper wires of the desk lamp directly in the outlet.

The desk lamp’s narrow spot of light made the room seem even more cavernous.

Restless, I opened the long green shutters: the street below was deserted and equally lonely. A fine mist hung in the air, making the dark scene below and the dim one behind me seem even more sombre.

There came a rap on the door.

In those days, even official Vietnamese hosts were not allowed to visit a westerner’s room. I opened the door to find one of the hotel staff.

‘Your friends are waiting for you,’ the clerk said. ‘Bring your jacket.’

I was surprised, for my hosts had already said ‘goodnight’.

‘Come on,’ one of my friends said the moment I appeared downstairs. Let me call her Xuân.

The other host, whom I’ll call Lan, opened the Unification’s front door. We had travelled to the countryside and around Hanoi City in a Russian jeep, which died every twenty minutes; the driver would resuscitate it, muttering as he blew the fuel filter clean. But this night there was no Jeep in sight; instead, two bicycles rested against the Unification’s mouldy stucco.

‘I’m stronger,’ Lan said.

I must have looked perplexed.

‘Hop on the back,’ she added. ‘And put your hood up.’

Two years before, I had persuaded the government authorities to let me ride a bicycle in the countryside, but, as strange as it may sound today, my hosts were afraid I might hurt myself riding a bike in Hanoi’s then mild traffic.

I had pedaled a bicycle much of my life, but I had never once ridden on the luggage rack.

I didn’t know what to do with my long legs, how to keep them off the ground, how to keep them free of the spokes. For the first time in my life I worried about my weight.

Vietnamese friends never tell me where they’re taking me, perhaps because they themselves already know or perhaps because they are veterans of the Resistance Wars, when Vietnamese didn’t even tell family members their destination. It seemed this night as if we rode on forever; my legs ached, my back ached. The streets were silent except for the occasional whisp-whisp of a passing bicycle. None of the riders seemed to notice the strange, hooded passenger moving through the darkness.

We stopped. My hosts led me down an alley, into a courtyard, up a dark flight of stairs, and into a small room. The room was dimly lit and bare except for a bed with a woven grass mat and bookshelves lined with tattered paperbacks in Vietnamese and French. I was invited to sit down at a low wooden table with four wooden stools. Xuân introduced me to her husband, whom I’ll call Bang. He rinsed tiny cups and poured tea. Smiling, he offered me a candied mandarin orange.

‘Welcome to our Tết,’ he said, and then he laughed. ‘Welcome to your Tết.’

‘Let’s get the watermelon’, Xuân said to Lan. Because of poverty, even official Vietnamese seldom travelled between their own major cities. Xuân had just returned from a rare work trip to Ho Chi Minh City, bringing back with her the prized fruit of Tết in the south.

Both women left the room. Suddenly I was alone with Bằng. At that time, Vietnamese were not allowed ever to be alone with a foreigner. Two or three or four officials accompanied every international guest. With the permission of the government, I had ‘jumped over that hedge’ in the countryside, where Xuân and I often slept in the same bed, as is customary in Vietnam. But this was Hanoi City. I panicked; I didn’t know what to do, what to say.

Bằng began to speak in flawless English, which he had taught himself by listening to the radio. He had not spoken English in twenty years. He was light-hearted, even funny. Soon Xuân and Lan returned, bearing a tray with artistically arranged wedges of fresh watermelon. That cold night in the north, we four relished the warmth of the south.

The fresh watermelon and candied mandarin oranges seemed so precious that I could only nibble at them, savouring sweetness as rare in that time of extreme poverty as our ordinary chit-chat was in that time before the openness we know today. The fourth night of Tết, we shared our delight in a friendship tinged by the impishness of having slipped out together through the darkness.

When it grew late, Xuân presented me with a bag of candied mandarin oranges for my father. She and Bằng walked with me back to the Unification Hotel. On foot, the distance that had lasted forever by bicycle was only a few blocks when taken step by step.

This Tết, I will ride my bicycle through the clamour of Hanoi’s motorbikes and taxis, enjoying the colours and lights as I go from house to house, visiting friends. It will be a precious time. I won’t see Lan because she has moved to Ho Chi Minh City, but I’ll stop by to see Xuân and Bang in the same house I visited that night in the dark of the moon before Hanoi became a city of lights. Although I’ll have a good time this Tết, I know no conversation will be as precious as that one in 1989, and no taste will be as exquisite as those nibbles of fresh watermelon from the south and candied mandarin orange from the north.

* Lady Borton is a well known writer about Vietnam. This article is reproduced from the book Frequently Asked Questions About Vietnamese Culture – Vietnamese Lunar New Year, general editors Huu Ngoc and Lady Borton, Thế Giới Publishers, 2008.