(No.7, Vol.3, Aug 2013 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

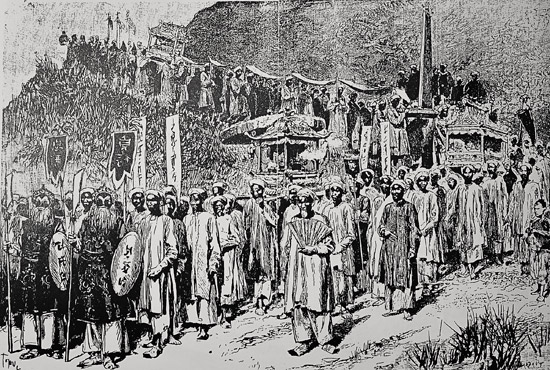

A funeral procession in Vietnam in 19th century. The photo is from the book ‘Vietnam in the past through French woodcut paintings’ (Vi?t Nam trong quá kh? qua tranh kh?c Pháp) published by Cultural and National Publishing House, Hanoi, 1997. Photo scanned by Nguyen Anh Tuan.

Funerals have always been important to the Vietnamese. Funerals express filial piety and respect towards the ancestors and set a moral example for present and future progeny.

Funerals are intertwined with the beliefs about spirits, which were originally believed to exist in all living things, not just humans. The need to venerate the deceased, forbearers, ancestors and other departed souls are ancient concepts in the East in general and in Vietnam in particular. They are believed to influence in no small terms the daily lives of the living. In Dragons of Annam (Con rong An Nam), King Bao Dai’s memoir, the king wrote, ‘In this country, the past manipulates the present. The dead influence the living — even more so than the living influence one another.’

An account of funerals in Can Huu Hamlet, Quoc Oai District in what was formerly Ha Tay (now part of Hanoi) during the years around 1966 reveals the meticulous preparation and dramatic execution of ceremonies for the recently departed.

On the road to Ba Vi, about 15 kilometres from the mountain, Muong culture clearly resonates in three old villages in Can Huu hamlet. The villages all have a community house, shrines, Buddhist pagodas, and many other temples. Elderly women adhere closely to the Muong’s style of garb: high baggy skirt, sleeved blouse, a storage sash tied around the waist, and a turban wrapped around the head.

Whenever someone in the village dies, especially an elder, a funeral is organized over three days. On the first day, people notify the authorities, set up a pavilion, and announce the news to kinfolk and villagers. Everyone in the village comes to give their regards and divvy up the work. Prior to 1966, during the days of the funeral, there was feasting, since people who came to pay their respects all brought food with them. The year 1966 was a time of war, so the expenditures for food and drink were cut and replaced with drinking of tea and chewing of betel and areca. On the second day, people hold the th?p ân (ten debts of benefaction) dance during the night. The dance includes a filial music ensemble that consists of a large drum, small drum, tall two-sided drum, nh? (two stringed fiddle), cò líu (high-pitched double string instrument), kèn loa (gourd-oboe), kèn lá (leaf-oboe), and a pair of cymbals. The main figure in the th?p ân dance is a young, approximately ten year old girl or boy, who wears a dragon cap and black garments with red hems and wields stringed-coin castanets as he or she dances while singing about the ten benefactions of mothers and fathers towards their progeny. When the performers dance, people can give tips by placing them onto a plate in front of the filial ensemble. During that time, the filial ensemble belongs to the locality and is allowed to eat with the head of the family. They receive virtually no wages, only gratuities.

A Vietnamese funeral procession in 1905.

On the third day, people select an auspicious hour during which to send the departed soul off into the fields. In front of the procession is a bonze along with a person bearing a pennon, which is fastened to a fresh branch of bamboo. This person is followed by a number of nuns holding Buddhist pennons and a few individuals walking around bearing plates that read Tiêu t?nh (stay silent) and H?i t? (keep back). Next come along twenty-three elders spreading a long piece of silk above their head—that is the ‘silk bridge’ that takes people down to the yellow springs (the netherworld). An elderly woman walks beside them, tooting an animal horn. Next come along a musical octet and people carrying pennons and parallel couplets. The latter were not very numerous at that time and usually just consisted of large pieces a fabric on which village Confucian scribes composed words of homage to the departed. The deceased’s oldest son dons mourning garbs and paces backwards incrementally in front of the palanquin. The coffin is placed in a magnificent dragon-palanquin, which is borne by up to sixteen people. After the palanquin comes the entire family. The daughters-in-law must collapse writhingly to the ground every few steps they take. Last of all come the fellow villagers. The palanquin procession dithers; every three steps they take, they then fall back one step. When the corpse is placed in the coffin, people usually drop a little money inside, which is referred to as the money for taking the ferry down to the yellow springs.

A coffin. Photos from the archive

of collector Philippe Chaplain.

After that, all of the deceased person’s belongings must be burned. However, at that time the economy was in difficulty, so a few days before the individual died, people moved the ailing person onto a narrow bamboo bed. They then burn the bamboo bed in the afternoon of the third day of the funeral. Overall, the funerals of ancient times do not differ much from those of today. They are very intricate with many fussy, solemn rituals.

In the book Vi?t Nam phong t?c (Customs of Vietnam) under the heading ‘Filial Practices,’ Phan Ke Binh wrote as follows, ‘In the village, whichever household has someone die must find betel to present and consult the Book of Changes. The family asks to appoint someone as a coffin bearer—or [it appoints] twelve, twenty-four, or thirty people; however many depends on the living head of the family, who leads the funeral’s filial devotions. And there are trays of betel to invite neighbours, clansmen, villagers, and the congregation of elderly women who escort the funeral procession.’

‘The living head of the household must don a staff and cap, go out to the community house, and kowtow to the village. Then, only after the village receives the prostrations, is the coffin bearer brought in to proceed with the funeral procession. Proceeding with the funeral procession requires having some customary money of several piasters in order to distribute it to the coffin bearers. In many places, a white fabric must be thrown onto the funerary house replica. Once the funeral proceeds, the fabric is distributed among the male villagers, one piece of the fabric for each person.’

‘Wealthy families and aristocrats often purchase their own exuberant funeral set and provide each of the coffin bearers several pieces of white cloth and a short white shirt so that they can proceed with decency. In the cities, markets usually gather to purchase an abundance of items for funeral processions. Whoever needs to come can enlist both people and funeral assistants. As for the countryside, the citizens buy a communal funerary set. Whenever a family in mourning speaks with the village inhabitants, the villagers have to appoint people for the funeral.’

Funeral proceedings that followed the old ways were actually quite costly and burdensome. Hence, Phan Ke Binh related that just because of these customs were born ‘living ghosts’ and ‘suffering ghosts.’ ‘Living ghosts’ were people still alive who worry that their descendants will not have sufficient money to perform burial rites for them when they die and end up owing debts to the village. Thus, they submit payments to the village in advance. ‘Suffering ghosts’ were families in mourning that had to fall into a verbal debt, in which they waited three years to come out of mourning and rebury the dead before holding burial rights and inviting the village in proper accord with the [usual] customs at the time of death.’

*Phan Cam Thuong is an expert on Vietnamese culture.