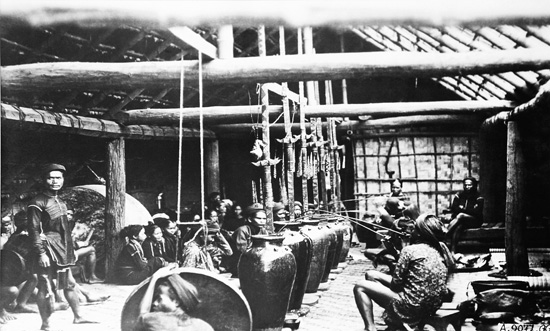

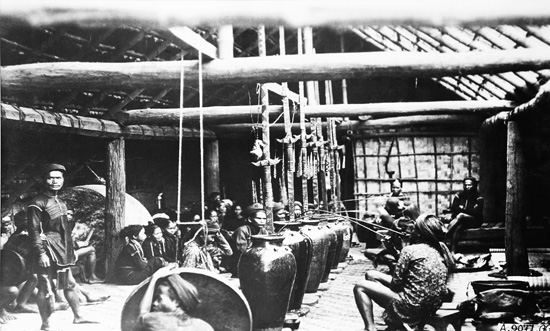

Picture: At an Ede longhouse in Dak Lak Province, a

celebration with jar wine and gongs and drums. Drums like the big one visible at rear left no longer exist in the

region of the Ede people, a note with the photograph says.

The photograph is taken by Nguyen Vuong and from a current exhibition at the Ho Chi Minh City Museum. The exhibition has ninety photographs, taken

between the 1930s and the 1960s, about the gong

culture of the montagnards in the Central Highlands.The exhibition brings together photographs from the Ecole Francaise d’Extreme-Orient [French School of Far East Asian Studies], the Quai Branly Museum, in Paris, and Missions

Etrangères de Paris.

Vietnam Heritage, September-October 2011 — Men in the Central Highlands are inveterate and untiring travellers throughout their lives. When a Central Highlander male is exactly one-month old he is placed in the middle of a reed mat and surrounded by three articles: a knife, a small piece of wood and a stick. His destiny is divined according to which item he touches with his hands. If it is the knife, he will be a fighter; if it is the piece of wood, which symbolise the staff of a leader, he will be a headman; and if it is the stick, he will spend his whole life as an arduous and steadfast wanderer on endless paths, in search of strange and good things in this existence. Of course, valiant fighters and renowned leaders are not lacking in the Central Highlands, but people say that most of the male newborn clutch the stick and are unwilling to abandon it. One of my close friends, who is from the Jarai ethnic minority, lives in a remote village, but I have caught him at home only once or twice in ten visits.

Male highlanders are in the forest for a large part of their lives, to stalk game, track a hive of honeybees, wade up a stream with many jagged or slippery stones in search of fish, cut logs and carry stones to block a spring to catch fish, patiently pursue a boar, an iguana, a lizard, or a bamboo rat. Or they may devote much time in looking for a beautiful tree deep in a virgin forest or high toward a peak, to obtain wood to carve a statue. Or they may stay at the house of a relative, old friend or any other wanderer like themselves that they have just made acquaintance with on the road, in an unknown and far-off hamlet, busily talking nonsense trivia and drinking rice alcohol from a jar through bamboo stems. In those moments they forget everything and pay no attention to place, time or the way home. The journey has then been transferred to another, different world, another space-time of forgetfulness.

In the Central Highlands man is not the root of life. In the continuous flow of generations without a beginning or and end, he is at best a certain thrust or a certain push in that sacred chain of being. Children there bear their mother’s name, and not their father’s. The Central Highlanders are matrilineal, not patrilineal.

In this region woman is the real owner of the flow, the master of life, the head of the family, the transmitter of blood to consecutive generations so that existence is not interrupted, not ‘forgotten’. Therefore, in the deepest meaning, man is forgetting, and woman is memory. She keeps the memory for the race.

In the Central Highlands a newborn baby is not a human yet. A soul to be blown in is needed for this transformation. Where to blow it in? Through the ears. In the ear-blowing ceremony. And the ear-blower is always a woman. She is usually chosen among those above middle age – is it for the endurance of the memory? She holds a coil of cotton thread, taken from a spinning wheel, and covers it with well-chewed ginger from her mouth, then puts the coil close to the ears of the baby and blows seven times while reciting the following prayer:

the nostrils become thorough

the ears become acute

the left ear

remembers the work

the right ear

remembers the fields

to be a human being, accept this human

soul

a boy

should remember the hoe

should remember the axe

should remember the lance to defend the

hamlet

the bow and the quiver

a girl

must not forget the wheel for cotton-spinning

the loom for fabric-weaving

the rake for grass-clearing

the basket for paddy-threshing

the water carried from the end of the hamlet

and the hearth warming mother and father

The word ‘remember’ is repeated many times. And the organ of memory, the means of knowledge and wisdom and the way to the soul, is the ears. We may understand that for peoples without writing, the oral language, hearing and memory are of utmost importance.

In all other ceremonies, the celebrant of prayers is a man.

The person with the sacred office of maintaining the memory of the race is also at the same time the fabricator of the most wonderful drug of forgetfulness in the Central Highlands: stem alcohol.

Stem alcohol is made of the most usual materials in everyday life: paddy, corn, manioc or any other cereal; somebody says millet is the best. These are cooked, pounded and rolled into balls.

The enzymes are concocted from the leaves, roots or bark of special plants. What kinds of plants is a women’s secret. They grow only in the most secluded areas of forbidden forest, where, it is said, there are girls, half-divine and half-human, whose main function is to enchant human beings and lead them into a world that is not so tiresome and mundane.

The enzymes are added to the process. The resulting substrate for stem alcohol is spread on a large, flat bamboo basket and covered under banana palms for three consecutive nights.

After the third night the woman of a cottage gently brings the prepared basket to the front door and wakes the enzymes up with a prayer:

wake up, enzymes

come on, wake up

you have already had a good sleep

now wake up, please

Gently, tenderly, the woman behaves like a mother waking her children.

Suddenly she gives the enzymes terrible ‘mission orders’:

enzymes, make them

vomit near the jar

defecate on the spot

men to unfasten their loincloths

women to drop their skirts

She continues to pray. This time the prayer is as if said by a male drinker of the alcohol prepared with the hands of women:

I pray the gods have pity upon me

I pray the gods bestow upon me

the favour of being lost in people’s homes

and sleeping with people’s wives

Where else in the world is alcohol given these formidable ‘functions’ and by women? Men are absolutely forbidden in the fabrication of stem alcohol. This is the restricted domain, world, secret and power of women.

Before putting the potion into the jars, the woman makes many circles with the flat bamboo basket on her arms or circumambulates, as in a dance, to render the drink more intoxicating, dizzying and vertigo-inducing.

Then, the closely-covered jars of alcohol, these dangerous and attractive time bombs along the walls or sometimes on the rafters, wait till they are solemnly taken out or down, tied to poles, uncapped of banana-palms, filled with clear water, and furnished with bamboo stems as drinking reeds.

Ecstasy of men and even women drinkers begins.

The women’s prayer goes on:

enzymes of alcohol

sweet, bitter, spicy and hot

make our ears split

make us forget the children a-weeping

forget to cook rice

for our husbands

Now we are in another world, another universe, where all prohibitions, taboos, and everyday rules are meaningless and everything is permissible. All is in confusion. Everything is upside down. Everything is erased. Bodies are mingled. And in the Central Highlands, during these bouts of drinking, a principle must be obeyed: everyone has to be drunk; nobody in sobriety is accepted; there must be no abstemious witness. All people together enter another world with a different set of rules: a world under the rule of forgetting.

The ears constitute the way to the soul, the gate of memory and the organ of wisdom. The opener of that way to a newborn is a woman and now the person who makes that sacred organ split, who leads people into the country of

forgetting close to the limits of the absolute, when people are on the verge of losing their personal nature, is a woman.

A few with profound knowledge of the Central Highlands and curious in their search for the secret of stem alcohol say that among the ingredients, multifarious and undisclosed, of the enzymes prepared by female witches, is one crucial element, galingale [a sedge with an aromatic rhizome, according to the Concise Oxford Dictionary, 2006]. Some even say that galingale is the very agent of drunkenness and absence of distinguishing heaven from earth.

Ginger and galingale belong to two very closely related plants, so close that they can be confused. Ginger opens the way of memory, while its sister galingale is the miracle drug leading to the country of forgetfulness.

It seems that in these awe-inspiring practices of the Central Highlanders there may be a philosophy. A life of total remembrance, without any forgetfulness, without some moments of forgetfulness, we cannot bear, in this human earth so full of sufferings, so complicated and confusing. Is it not true that this existence has moments worthy of being forgotten for good, as well as valuable ones worthy of being remembered?

[Is this what is behind the ‘splitting’ in the woman’s spell? Could it be called sorting, or discriminating? – Ed.]

* Nguyen Ngoc is a well-known writer and expert on Central Highland culture.

The author acknowledge with gratitude data

collected by Jacques Dournes, a French

anthropologist devoted to the study of the

Central Highlands Vietnam.