(No.8, Vol.6,Oct-Nov 2016 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

Within just three km2, there are two national cultural relics, a famous beach with pebbles of seven different colours, and a temple for those who perished in a bloodcurdling massacre 60 years ago. A day scouring on foot the tiny piece of land packed with heritage in Binh Thanh Commune, Tuy Phong District, Binh Thuan Province seemed as long as years.

Seven-coloured beach

Leaving the inn early in the morning, we came to a shop that sold the typical cang cake of Tuy Phong. The shop keeper was filling and changing the red hot cake moulds in the oven at dizzying speed. The shop was so crowded that we had to leave, missing a chance to enjoy a mouth wetting, VND20,000 local breakfast.

A few hundred steps further, we came to the beach, thick with shops that sold food and beverages, all crowded with tourists in a good mood.

Behind the beach, the famous seven-coloured pebble field looked like a levee built with pebbles. The ‘levee’ was over one kilometre long. Scientists say that this 250,000 m3 pebble field was formed by an irregular sea current that pushed the pebbles here from the bottom of the ocean.

The waves continuously lapped on the levee and then receded. Over thousands of years, this made them sleek and shiny under the sun.

Unable to resist the temptation, we removed our shoes to walk on those gems. The touch, the sounds and the air made the foot massage feel magical.

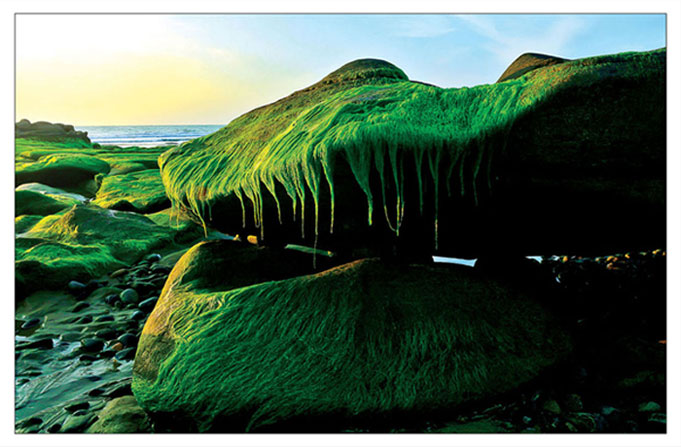

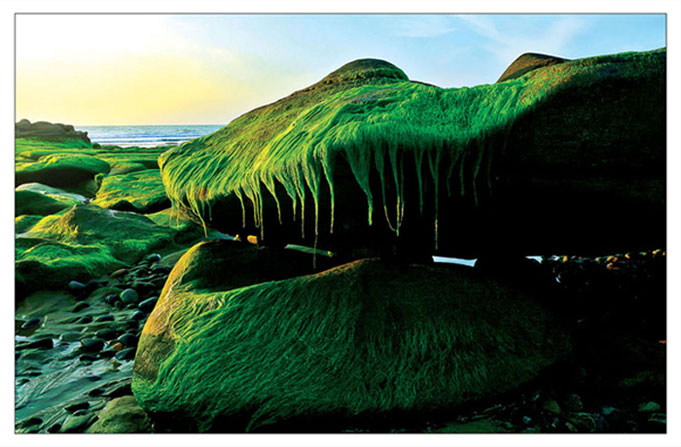

After the seven-coloured pebble field, we came to a rugged rock formation which was green as if painted. I have been told that this phenomenon happens only during the months of February-March, attracting a lot of photographers.

Pagoda in a cave

About 500 metres from the seven-coloured field, we came to Co Thach Pagoda, the most sacred pagoda of Binh Thuan Province and a national cultural heritage site.

This is actually a complex of an old and a new pagoda besides the one in a cave, with many Buddha statues standing on big rocks scatted around the five ha premises of rugged terrain edging the sea.

It took quite a lot of sweat to see everything in Co Thach. We had to not only go up and down the rocks, but also worm ourselves through rock slits and creep into pitch dark caves.

The oldest building here is a small pagoda built 150 years ago under the shade of age-old trees, surrounded by enormous rocks stacking on one another. The space between these rocks form caverns, each houses a Buddha statue and is always incensed. The locals call such caverns ‘Cave pagodas’, and there were many of them on this hill.

The website of Vietnam Buddhist Church describes the founding of this first ‘cave pagoda’ as follows: ‘In the mid-19th century, Zen priest Bao Tang chose a rock cave at Co Thach to be his place of meditation. Admiring the monk’s spiritual achievements, Mr Ho Cong Diem built for him a spacious pagoda and named it Co Thach. Since then, Co Thach pagoda has gone through four generations of venerable head priests and multiple renovations…’

The 300-year-old communal house

That noon, after a modest VND25,000 lunch, we took a one kilometre walk to Binh An Village’s communal house, recognized by the government as a ‘national heritage of artistic architecture’.

The house has the blue sea at the front, the fishing village at its back, a dock with hundreds of anchored fishing boats on the right and a white sand beach on the left.

The main structure of the house is a group of three interconnected, mostly wooden buildings, which are the Main Sanctuary, the Middle House, and the Kowtow Hall, having an area of 300m2 in total. Culturologists say that this house is a “nice mixture of palace and folklore architectureâ€, which is used to worship deities and national heroes.

All pillars, beams, purlins and walls of these buildings are meticulously cut, carved and polished. The portal of the Main Sanctuary bears intricate relieves of the sacred animals: a dragon, a unicorn, a tortoise and a phoenix; a conifer and a reindeer representing long-lasting fortune; apricot blossom representing wealth; and cranes as symbols of longevity.

Inside the house of Binh An, there are tens of altars of different sizes, all beautifully carved, and precious antique utensils such as bells, thuribles, weapons, drums, wooden bells, a great bell, and silk conferment letters of the Nguyen Kings.

The whole 1,500m² premises is fortified by a strong one metre thick and 2.5 metres high wall. The main gate is three metres high, 2 metres wide beneath a gate sign that reads ‘Gate to the marvel’. It is adorned with ‘two dragons competing for a gem’ statues; Lord Silk Fiber holding the Sun and Lunar Lady holding the Moon statues representing the harmony of Ying and Yang…

The green moss season in February to March, in Co Thach, Binh Thuan Province

Photo: Nguyen Bao Son

The story of a horrific massacre

That afternoon, when the blaze of the land called a ‘little sand desert’ was subdued, we took a 2.5 kilometre walk from the communal house and came to the memorial of the massacre that shook the world 60 years ago.

The inscription at the memorial read, ‘Morning, February 20, 1951 (a full moon day of first lunar month), a French regiment marched into Cat Bay Village and opened fire, killing 311 villagers, burning hundreds of houses and raping many women.’

A cave pagoda in Co Thach, Binh Thuan Province

Photo: Dang Khoa

After burning incense and praying for the hundreds of innocent souls, we entered Cat Bay, a poor and peaceful village beside the memorial. Some people here still remember the tragic scenes and events that took place ‘That morning my family was having cassava for breakfast. Suddenly, we saw a lot of legionaries surrounding the village. A group of soldiers came to our house and shouted, “Everyone out!†12 members of our family held each other inside, trembling from fear. They immediately opened machine gun fire and burned the house. I was 16 at the time, and was holding a little brother behind a bag of rice, and that’s why we survived,’ recalled an 80-year-old man named Thoi.