(No.7, Vol.3, Aug 2013 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

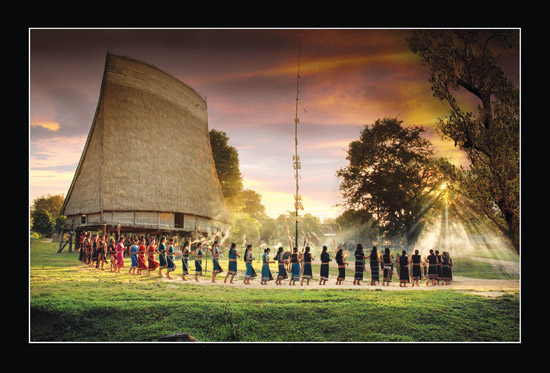

A Rong house (communal house) in Dak Rowa

Commune, three kilometres Southeast of Kontum City, Central Highlands, 2009.

Photo: Nguyen The Duc

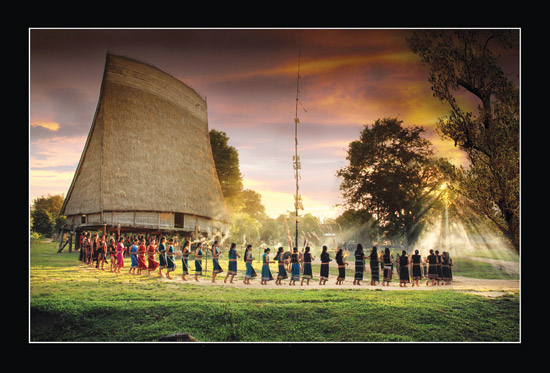

A Rong house (communal house) at Quang Trung

Museum, Tay Son District, Binh Dinh, South-Central Vietnam, 2011.

Photo: Bui Dac Ninhthap-Lycee-Yersin-Dalat.jpg)

College Yersin in Dalat

Photo:Nguyen Hang Tinh

Banh It 5A, a Cham tower in the South-Central

Province of Binh Dinh

Photo: Nguyen Ba Ngoc

The bell tower at Thien Mu Pagoda in Hue

Photo: Nguyen Ba Ngoc

Banh It A, a Cham tower in the South-Central

Province of Binh Dinh

Photo: Nguyen Ba Ngoc

However many times I’ve been in the northern part of the Central Highlands, that’s how many times I’ve been taken aback by the proud and majestic rông communal houses of the local Xo Dang ethnic minority. Everywhere you look, you see architecture that resembles knives or axes thrusting through the forests, cleaving into the azure sky above, and that’s how you know a highland village exists below. The Xo Dang and Ba Na people of the mountain plateau are as unsophisticated as the trees and plants. The place where you squeeze in and out of the stilt houses is also as gentle and mild as a brook. Yet I cannot fathom how, since time immemorial, these people created such mighty silhouettes as those of the rông communal houses. Could it be that they wished to assert their meager human presence before the wilderness and the immense jungle?

Going along with the flow of my obsession, I recalled Nh?n (Goose) Mount in the Tuy Hoa lowlands of Phu Yen Province, South central Vietnam, the glistening rice-green place with Cham temples. There the vivid clayish-red Cham temples stand loftily looking out to the East Sea. The people of Tuy Hoa feel proud whenever they say ‘ascend to Nh?n Tower!’ A little to the south is Khanh Hoa Province with Po In? Nagara Tower. Coming back a bit, you enter Phan Rang, a city that shoots up amidst sunny sands and cacti. Regardless of where you stand or in which direction you face, you can see Po Klaong Garai Tower, despite its having come into existence back in the thirteenth-century. When the Cham kings’ power expired, only that silhouette remained steadfast through the passage of time. No throne is powerful enough to challenge time and history, yet the silhouette defies sun and rain as well as typhoons in the harshest land in the country. Also, It is hard to remain unaffected by the bell tower of Thien Mu Pagoda in Hue as well as the Chàm Bánh Ít and Duong Long Towers in Binh Dinh Province in the South central region. Standing in the misty mornings at Ong Dao Bridge or Cu Hill in the Langbian highlands of Dalat and looking far out to the southeast, one is thunderstruck by the unbelievable resplendence of the Lycée Yersin Secondary School Tower reflecting in Xuan Huong Lake. The tower rises above the tops of pine trees, yet is not outshone by the hues of the forest pines as it reposes firmly, wanting to etch the aspirations and intelligence of mankind onto the azure highland sky.

Many Dalat people often send those travelling afar a photograph of the Lycée Yersin Tower, as do the people from Phan Rang and Po Klaong Garai.

Mankind consciously selects ideal lands on which to settle. Architectural creations have thence been situated on mountain peaks, elevated hills, or on level lands, where mankind nonetheless exerted its wealth and intellectual talents to elevate them into the cerulean sky. They are solitary in their loftiness — solitary with intent and human creativity. They are not nature’s creations, but they are in harmony with nature. Each of these towers seems to have delicately descended like a rain drop from the empyrean, and each one is each a bead of fond longing that rends the heart.

The silhouette gazes down on the homeland, on time, on the era, on history, on joyfulness, on sorrow, and on the sufferings of mankind on the earth below. It shoots up into the blue sky so as to peer down loftily at the vast expanse of the homeland. The silhouette is the soul of the homeland; it is the purview that first espies a conflagration, a joyous day of victory in war, a festival, or a battle — just as a nascent storm, the very first drops of rain, unfailingly pour first onto the silhouette. In the same way, none other than the Silhouette is the entity that parts last with the passing storm in the homeland and decries the desolation of myriad living creatures below. Yet the silhouette is also the first place to greet the immaculate light of the matutinal sun. Thus, refined and reposed architecture that strikes its mark in the soul becomes a symbol of a city or native village.

Many thousands of years of human history indicate that on the heights of the native land, should a church bell tower, a Buddhist pagoda, a tutelary shrine, a school tower, a museum, or cultural structure appear, it pleases the eyes and salves the hearts of men more than a fuming lime furnace, a water reservoir, a sentry tower that keeps watch over enemies, a moon-gazing spot for lords and kings, or a private resort reserved for a small, wealthy and powerful segment of the community to throw lavish parties. When people have yet to build anything on such elevated sites, the most ideal space and setting of a given place, perhaps they do not yet possess a soul or, if they do, it is a pre-nascent, unseen spirit that is in accord with folk sentiments and beliefs. Thus it can be seen that religions have, since time immemorial, been exceedingly sensitive and profound towards silhouettes. Whenever churches and pagodas were erected, they were built on mountain peaks. Moreover, royal dynasties, lords and kings, and then even wealthy, high-cultured individuals all desired to create silhouettes. However, that which belongs to the community and which is inclined towards the common people is compassion and vitality.

It is truly fortuitous for such lands to possess the figure of a silhouette, since the genesis of its image is like a marriage between nature and the intellectual talents of humankind that seems only rarely encountered in Vietnam. Many cities in Vietnam have a thousand years of history — or 700, 500, or 300 years of history — and yet still lack a silhouette. Hence, in many provincial cities and villages, when people think of the homeland, recall makeshift stalls, streets, rows of trees, stone benches, courtyards, ferry wharfs, rivers, or bridges — or they just recall the entire city. To indicate their cultural mark, all such recollections possess their own brilliance, but not a silhouette, the desired piquancy of any urban dwelling. How strange! The silhouette is something with a month and date of birth and an author, yet in the eyes of sentient beings, it belongs almost entirely to common folk. And whatever belongs to the common folk is something that consists of shared devotion. People of the world are not compelled to know the author of the silhouette, but from it they can sense sentiments of the homeland with each dawning and dusk, from the dawn of nature to the twilight of human life.