No 3, Vol.10 , September – October 2015

The book in a closer look

Following senior lieutenant Nguyen Khanh Toan of the Cha Lo border patrol outpost, I came to visit Mr Ho Thoong, born in 1962 at Ha Vi Village, Dan Hoa Commune, Minh Hoa District, Quang Binh Province, owner of two century-old books of the Khua people.

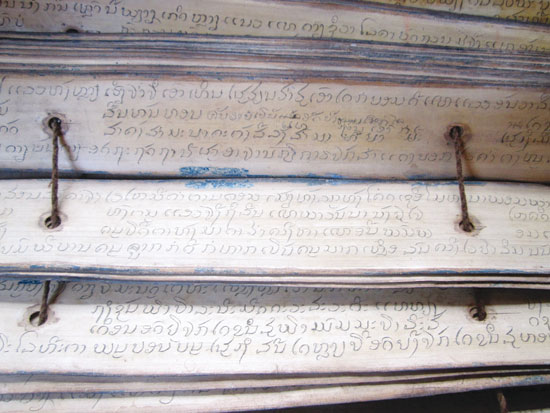

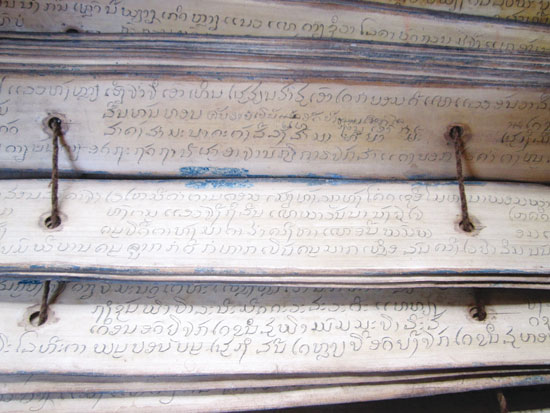

Even Ho Thoong himself doesn’t know how the books were made. He only heard from his father that the Lao people call the palm-like leaves, used to make these books, tan or buong. They tie young leaves on the trees to not keep them from spreading. Only this way will the leaves grow tough enough to be used for books. It took years to write a book like this, so their number can be counted on fingers.

After being tied to a tree for a year, the leaves were sun-dried. The ink they used was Chinese, mixed with the gall of a species of fish which only lives in the creeks.

To write, they sharpened a piece of iron, dipped it into the ink, and carved on the leaves which are thin but very hard.

The book kept by Ho Thoong is about 50 cm long. It has 50 pages, which are about 5 cm wide; each contains 4 lines of text.

The other book is about 60 cm long with 200 pages; each contains 4 lines of text. Ho Thoong has submitted it to the Cha Lo International Border Gate Patrol for research.

Ho Thoong said, ‘This book was left by my great grandfather. As a child, I saw my grandpa read it and use it to teach my father.

In the turmoil of war, my father followed the revolution and forgot to teach his children. Before dying, my father told us to cherish these two books.’

According to some elders of the village, the books record the origin, history, culture and customs of the Khua people.

Mr Ho Thoong

They also contain good and righteous things, ethics, experiences about the soil and weather, lessons of planting and harvesting that the ancestors wanted to pass to their descendants.

But according to 110-year-old Ho Ket of Y Leng Village, books of this kind record prayers used for funerals and worship rituals, much like those of the Viet people.

Passed through many generations, having witnessed wars, floods and migrations, the centuries-old books and the ink in them still look fresh.

Although Cha Lo International Border Gate Patrol and the Ethnicity Committee of Quang Binh Province have borrowed a book to study, until now its content is still not decrypted.

‘I would very much like to read what is written in the books. If not I, then the following generations will do it. We are determined to keep them because they are the dear heritage that our ancestors left for us,’ Ho Thoong said.n

*The article appeared in a different form on Vietnam Net, 21 December, 2014