(No.5, Vol.4,Jun-Jul 2014 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

Sinh painting Photo: Hoang Huu Tu

In Vietnam, it was not until the twentieth century that printing houses began employing Western methods that used machinery and printed fine lead letters. Five hundred years earlier, the means of producing printed materials was truly no simple matter. People in the past also realized how problematic this was. Thus, important sutras, books, and historical hallmarks—anything which people wanted to promulgate to the populace—were engraved on bronze or stone steles. Anyone could attach a paper to the stele, apply ink, and pat the paper down gently and gradually from behind. The places with inscriptions would come out white, while those without would come out black. Following this method could result in a picture. It was not used to make a prose document, because the document would always depend on the size of the stele, which was usually very large.

Bronze-blocks at Sinh Village, Hue. Photo from Vietnam Heritage Photo Awards 2012. Photo: Hoang Huu Tu

Later on, the xylographic method of printing developed according to the two styles of supine printing and prone printing. Supine printing was pressing paper onto a woodblock print that had been coated with ink and placed on the ground (or held in the hands, as Dong Ho paintings are printed). After that, a loofah sponge was used to rub the paper so that the features of the lettering would be imprinted. Prone printing was putting the paper down and pressing with the woodblock print from above. This method was often used by graphic painters. They had to design an entire mechanical press to push forcefully and deeply into the paper before the ink would penetrate. This method was appropriate for printing detailed paintings, since the details were printed onto the paper very carefully.

A print from a recently-restored 16th century woodblock.

Photo provied by Nguyen Anh Tuan.

However, as for the printing of books, this was too cumbersome and slow. People in the past often used Chinese ink mixed with plaster or glue. Printing with Chinese ink was relatively difficult; it bled easily and was wasteful. The Vietnamese created a kind of ink that allowed for just one application of ink and one printing to produce black, well-featured lettering. Even Dong Ho and Hang Trong folk paintings were done like this. This black color was made from bamboo or straw, which was lightly burned so that its qualities were retained and then soaked in a jar until it became muddy. When used, it was necessary to mix a sticky paste, which was poured into the ink, so that it fermented for a few days. Depending on the weather, the fermentation caused the ink to become very dark. When it was time to print, the sticky rice paste was again stirred and poured in the ink to make it sticky. The sticky paste kept the vegetation-based ink from bleeding on the paper. At the same time, it ensured that the printing only required one application without having to do it again a second time. Nevertheless, if printing a picture, the colors needed to be applied up to four times before it was dark enough to render it in detail. After having printed several times, it was necessary to clean the woodblock, because if the ink got too sticky, then it would no longer come out detailed enough.

Bronze-block at Sinh Village, Hue.

Photo from Vietnam Heritage Photo Awards 2012.

Photo: Hoang Huu Tu

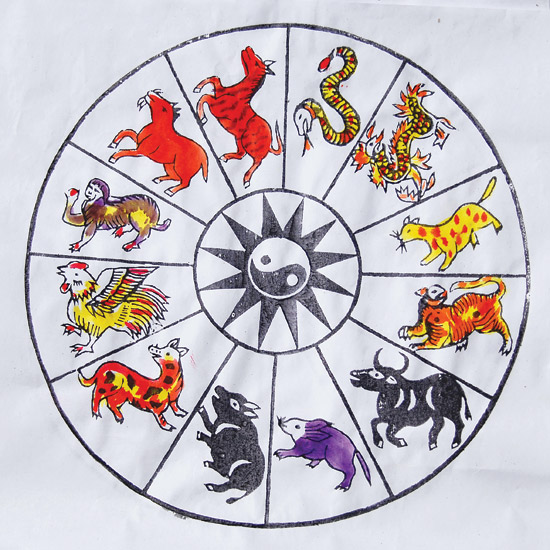

If the woodblock was used to print books, then there were only black and white woodblock prints. When printing a multicolored picture, then it was necessary to use quite a lot of woodblocks to print in color according to the number of colors and shades in the picture. Dong Ho folk paintings did not have light and dark shades, but rather are printed in the original colors. The number of color woodblock prints was not great, only four to six of them. Chinese New year folk paintings have both original colors and places with multiple shading, so the number of color woodblocks is greater. However, unrivaled in the use of multiple coloration was Japanese Ukiyo-e painting, which had up to sixty-four color woodblock prints. Thus, in order to print out a picture for which each woodblock might have color applied three times, it took up to and over 200 printings. In order to make all the woodblocks match one another without bleeding demanded extreme expertise in printing. Owing to this, painting colors by brush became prevalent, especially in the New Year paintings and folk paintings of Hang Trong, Kim Hoang, and Sinh Village. That is, people printed out the black features onto the paper and then painted on colors with brushes. This process was just like painting; thus it was possible to tinker with the shading.

Painting and drying at Sinh Village, Hue

Photos from Vietnam Heritage Photo Awards 2012.

Photos: Hoang Huu Tu

Fading a gradient from dark to light was very common in New Year and Hang Trong painting. Nowadays, some Dong Ho paintings also utilize this method, especially in the four seasons set of paintings. In the Hang Trong painting tradition, people used a flat brush and dotted a corner with ink while dotting another corner with water. The black ink and the water bled together to create a light to dark gradient. Then people could facilely paint shades onto the paper. All folk paintings that were painted by brush used natural watercolors or pigmented colors that were applied very quickly. Sometimes people finished applying the colors to a painting in just ten minutes. It is not true that all folk paintings were xylographic prints. In fact, in the past, many painting studios painted entirely by hand and the artist painted right in front of the customer. Of course, all the subject matter was familiar— religious devotion, just as the men of old had painted and passed down to them.