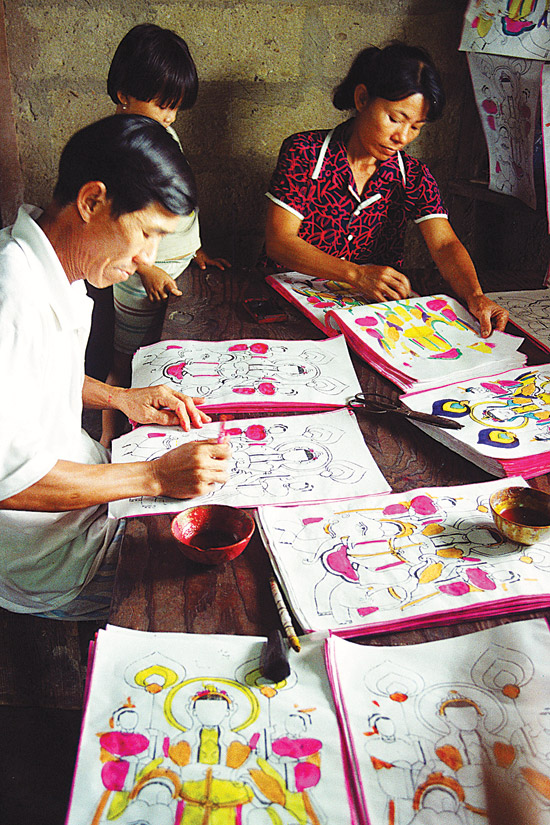

(No.3, Vol.4, Apr-May 2014 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

Painting at Sinh Village

Photo: Pham Van Ty

Among the number of folk painting villages that still exist, Sinh Village is considered one where the craft of painting remains associated with the belief-based activities of the common people. Sinh Village, also known as Lai An Village, belongs to Phu May Hamlet in Phu Vang District, about 9km east of the city of Hue. Lying at the confluence of the Bo and Huong Rivers, the village favourably facilitates commerce, and its Sinh Village paintings seem to command the market throughout the provinces of Central Vietnam. Nevertheless, the paintings are most prevalent in Hue, where they even appear in the Forbidden Palace and in the votive rituals for siring an heir among the folk populace that are discreetly organized by senior women alongside orthodox palace ceremonies. Sinh Village is not only renowned for the craft of painting, but it is also an ancient village with Sung Hoa Pagoda, which is famed for its records of history from the sixteenth century. The village is moreover well-known for wrestling festivals and the trades of making incense and roasted kernels as votive offerings. Perhaps it is because of these traditions that the craft of printing xylographic paintings in Sinh Village, right from the time of its inception several hundred years ago, has not been purely a tradition in service of refined amusement, but rather chiefly of the belief-based needs in which the paintings are used to worship, to burn in votive rituals for well-being, and to extricate people from unpropitious fates.

As for the subject matter of Sinh paintings, they are divided into three major genres: portraits of personages, animal paintings, and paintings of objects. The portraits of personages are usually those of people who sacrificed their lives for others or ‘destiny paintings’ of the venerable gentleman, gentlewoman, or cook—that is, the deities of fate who watch over the head of the family. This type of painting is usually affixed to walls and is not burned until the end of the year, whereas all the other paintings are burned as oblations along with gold and silver votive objects once the prayer offerings are complete. The animal paintings are those with printed images of the twelve worshipped zodiac animals or paintings of kinds of domestic animals like buffalos, cattle, swine, and horses that are hung in breeding pens so as to pray that the animals will avoid disease or will bring prosperity in business. Pictures of spiritual beasts like elephants and tigers are used as offerings in temples in order to pray that they will not bring calamities down upon humans. The paintings of objects are types of clothing, implements like bows and arrows, or offerings like the garbs of gentlemen, gentlewomen, and soldiers that are printed in decorative patterns.

Drying paintings

Photo: Trang Thanh Hien

In terms of technique and materials, Sinh paintings are similar to most ancient folk painting traditions like Dong Ho and Hang Trong in the North with their method of woodblock printing, which involves fairly sophisticated steps; carving the woodblock print, printing out the picture on ‘noble scallop paper’ (gi?y ?i?p), and then painting in the colour. Sinh Village was, in the olden days, also referred to as the village that made paper pasted with noble scallop shells, which were not only used in printing paintings, but also in other trades. To print in colour, mostly materials inherent in nature were utilized. After that, a strict treatment process was undergone so as to make sure the colours did not fade after application.

The obtaining of the dye materials, too, bears a characteristic semblance to Dong Ho paintings, but they also involve local products and folk experience in order to achieve various nuances. Whereas the colours of Dong Ho paintings generally only consist of a few basic colours that are overlapped with colours from different kinds of woodblocks so as to render the paintings’ colours multifarious, Sinh Village paintings resemble Hang Trong paintings in that only one woodblock is printed in black lines, after which colouration is painted in in detail. The method of painting colouration is usually done in level layers and painted in monochrome; rarely are they painted in overlapping colours. They are also not painted in the manner of selecting dark and light hues by mixing added water so that the colours produce a pronounced sheen like in Hang Trong paintings. It is precisely this characteristic that ensures that the colours of Sinh Village paintings must be prepared with greater hues.

Woodblocks

at Sinh Village

Photo: Phan Thanh Binh

Take the colour yellow, for instance. Whereas Dong Ho paintings only have flamboyant yellow, Sinh paintings have, in addition, a yellow hue from Dung tree leaves. These two hues are mixed together to create a yellow colour that is more sedate and also more solid. The colour red is made from the bark of willow trees and leaves of the tropical almond tree (Terminalia catappa) or myrtle wood, which are cooked in water until they condense down and thicken. The colour green is mixed from two kinds of juice that are extracted from star gooseberry leaves (Sauropus androgynus) and yanang leaves (tiliacora triandra). Purple is made from finely ground basella alba seeds that are pressed into alum water and mixed with kali alum in order to retain the colour. The colour indigo is made from cajuput leaves that are seeped in lime until they decompose. This is then beaten into a foamy pump, after which the foam is scooped out and finely filtered. Then water is added and condensed until it thickens. The colour grey is made from ramie leaves that are dried, finely ground, and simmered down into an extract. The colour black is a blend of tropical almond tree leaves that are pulverized and closely incubated with straw ash.

A French student prints a painting at Sinh Village

Photo: Trang Thanh Hien

Even more peculiar are the brushes used to paint Sinh Village paintings. They, too, are among the local products. The brushes for slaking colours are usually made from rua roots that are cut at a certain time of the year. After that, they are set out to dry and peeled to leave only the inside part, which is just fibrous and soft enough to take up ink for applying colours as does a hair brush.

As for the Sinh Village paintings of old, although they were votive objects to be burned, their exquisite features were nevertheless clearly evident. In particular, the set of ‘Eight Tones’ paintings (tranh Bát âm), which was one of the rare painting genres that could be used to hang up for pleasure in this painting tradition, required exquisiteness to carve the woodblocks as well as to paint in colouration. We can see in the fine women’s clothing the sophistication in every detail, from flower buttons and hairpins, to the patterns on the coins, the character for ‘Longevity,’ the women’s shoes, and the musical instruments they hold in their hands.

When comparing the style and appearance of the clothing in paintings of the venerable gentlewoman to those in the painting tradition of the Mothers Cult in the North, we can gather the features that are similar in arrangement. However, in spirit, they are entirely different. The sophistication of the manner of bracelet jewellery and the embroidered laces of the ‘shoulder clouds’ that shroud the shoulders of these regal women are characteristic of two styles of clothing from two regions. The headscarves that cover their heads, as well as those of the servants are also very sophisticated. Nevertheless, in recent modern woodblock carvings of Sinh Village paintings, due to the level of the artists as well as the obscuration of the trade village, these sophisticated details have been greatly simplified. And yet, echoes of the aesthetic style from the land of the capital still seem to linger.

Moreover, whereas in the Dong Ho and Hang Trong paintings, we can vividly see the features of Chinese cultural influence in a number of subjects or styles of painting, in Sinh Village paintings, these elements have, perhaps, become more pure. The sophisticated character and influence from the art of palace raiment is clear, but they are entirely extricated from the Chinese. Especially in paintings of animals and objects, a wholly folk aesthetic style and vision is borne out. The boorishness in creating images is merely such that people are able to recognize what creatures they represent. They are not stylized or created to graphic standards.

Today, in the spiritual lives of the people of Hue, Sinh paintings remain present as if indispensable. However, the former flavour and spirit of a time when they once flourished seems to no longer exist. The ancient woodblock sets were lost with time and rotted away with the flood seasons every year. In addition is the appearance of many ostentatious paintings and sculptures among Chinese high-caliber votive objects that cause the day-by-day obscuration of the painting tradition. Furthermore, due to the provisional character of paintings that are just made for votive burning rather than being hung up for amusement the way Dong Ho and Hang Trong Tet paintings are, the generic and cheap character of the raw materials make for the increasing preference for such paintings.

* Phd Mrs Trang Thanh Hien from Hanoi is a researcher on Vietnamese ancient art