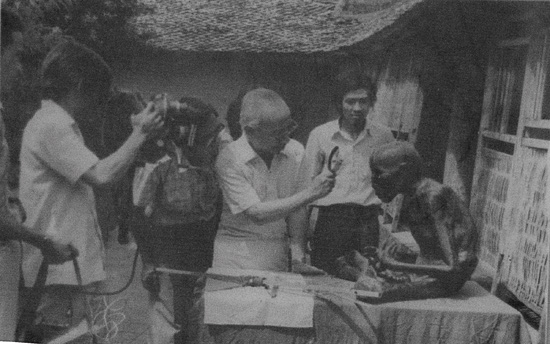

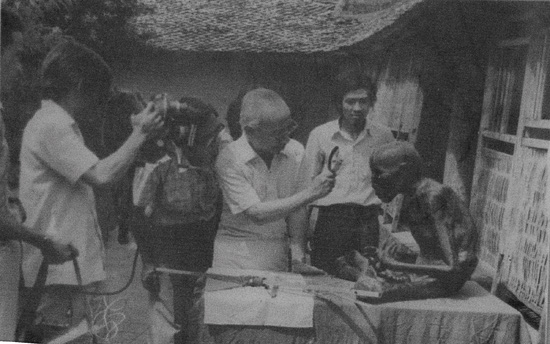

Above: a photograph of the late Pham Hung Thong, head of the Institute of Archaeology, and colleagues with the mummy statue of Zen master Vu Khac Minh in 1983. The photograph was in the pagoda and photographed by Dan Ton

Vietnam Heritage, February 2011 — On 3 May 1983, I was a member of a group the Institute of Archaeology sent to the Dau pagoda, about 24 km from Hanoi, to inspect the condition of the bell-tower. Wandering towards the side of the pagoda I saw a small hut covered with moss. I was startled to find a monk sitting with crossed legs, eyes half-open, as if pondering the Buddhaland.

For a long time people in the region had been telling a story about Zen master Vu Khac Minh, who presided at the Dau pagoda in the 17th century. According to the story, it had been reported a long time ago: ‘The other day he stepped into the hut and said to his disciples, “Bring me a jar of fresh water and a jar of lamp oil. Open the door as soon as you hear the wooden bell stop. If you find my body decayed, block the hut, otherwise cover my body with paint.”’

Looking through a crack in the statue’s forehead, I saw a skull inside. I would have the statue x-rayed to prove that this was the original physical body of the master.

On 25 May 1983, I moved the body of Zen master Minh to the x-ray laboratory in the Bach Mai hospital. Evidently there was not any glue between the vertebrae and the spine and ribs were in the logical order but in the belly area. The skull was perfect. The top had not been chiseled to take the brain out (which is often seen, an example being the Egyptian King Ramses). It could be concluded that the brain and other internal organs remained inside the corpse.

From combining slides and x-rays, it was clear that the bones below the skull, such as the humeri, wrist-bones, metacarpals, hip bones, femurs, tibias, fibulas, cuboid and metatarsals, were in their correct anatomical positions. These bones didn’t have metallic cores. Using various methods, Dr Le Nguyen Soc confirmed that the body had been strengthened by a combination of natural paint, sawdust, paper and dirt.

I was excited I had proved this was a new [to Vietnamese archaeology] mode of burial, the ‘statue burial’, where the dead body is made into a statue, or the ‘Zen burial’, where the body sits with crossed legs. Some time later I came to know that this custom existed in China too.

In the pagoda there was a second statue, this one of Zen master Vu Khac Truong, Minh’s successor.

In 1893, the pagoda was flooded and the statue of Zen master Truong collapsed. The elders in the village had to build another statue using paint and a bamboo-and-wood frame that would house the bones.

At the Institute of Social Sciences Information in Hanoi, we found photographs of each of the statues. In the picture the statues were still in good shape, and they didn’t appear to have any cracks.

The statues were left neglected in a cottage next to the pagoda for a few dozen years. In the very humid climate, both statues deteriorated. There was a crack on the knee and the face of the Zen master Minh statue. The bottom of the Zen master Truong statue was broken and the statue wouldn’t sit upright unless placed on a board.

I started working on a conservation plan at the beginning of the year 2000. The working group consisted of me, as director, an artist, two sculptors and an engineer.

On 18 April 2003, a ceremony took place in the pagoda, beginning a hard job that would last six months.

We applied traditional techniques of casting, cutting, cushioning, polishing and gilding. The materials included paint, cloth, mulberry paper, sawdust and dirt. We put 14 layers of paint and gilding on the original statue of Zen master Minh. We covered the Zen master Truong with silver. After a coat of paint, we polished the statue. On the last coat, after we had varnished it, we found that the surface was still not smooth enough. Dust had stuck to the surface. We decided to work over again, this time inside a mosquito net.

Photos: prof. Cuong

The statue of Zen master Truong, which had been rebuilt before, had several details wrong. [At one point] I thought I would dismantle the statue, collect the bones, then, based on the skull, restore the original face. I studied this method, used by a Russian, Mr Gherasimo, and I was the first and only Vietnamese to go abroad for further studies in this area. The people in the pagoda and the local government officials did not approve. They thought the people in the area had the image of Zen master Truong imprinted deep in their minds. Even if the statue could be rebuilt to look exactly like the original physical body, they would not accept it. I had to follow their ideas, despite the pent-up anger developing in my mind.

The statue had serious damage and the coat of paint on it was totally decayed. A bump could make the whole thing collapse. Therefore we could not make a plaster cast of the statue to make a copy for reference. But we made a copy statue

in clay.

On a summer afternoon I was looking at the original statue of Vu Khac Truong when I noticed its arms were disproportionately long. I secretly made four holes. At the right humerus, close to the shoulder, I discovered a pulley, and the humerus was in the wrong direction. A fibula [shin-bone] had been inserted into the humerus.

We covered the statue with paint, tissue paper, cloth, sawdust, dirt and silver I have been mentioned. The thickest part came to as many as 22 layers. The whole statue of Zen master Truong weighs 31kg.

Whoever visits the Dau pagoda will see two identical Minh and two identical Truong statues. The originals are in the pagoda and the copies, made of plaster, are in shrines next door.

The restored Vu Khac Minh enshrined at the Dau pagoda

This article appeared in a different form in Thanh Nien in late 2010