(No.7, Vol.2, July 2012 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

It was the most beautiful village of the

Bahnar I had ever seen, and gloomiest. No smoke from kitchens, laughter of innocent children or sound of women pounding rice with mortar and pestle. Nothing, at noon, except a rooster crowing.

In 2002, Kon So Lal Village, Ha Tay Ward, Chu Pah District, Gia Lai, Central Highlands, was relocated closer to the centre of the ward, the reason, according to the President of Ha Tay Ward People’s Committee, Dinh Suk, to give the villagers better living conditions, in a place where, according to the province’s policy of ‘??nh canh, ??nh c?’ (‘Stable work, stable life’), they would have better access to electricity, roads, schools and medical services.

Five of the oldest villagers remained in the old location.

The old village was about 50 houses on a broad flat surrounded by forest. They were on stilts and had reliable wooden floors. There were a couple of tiled roofs and the rest were thatched. The walls were of bamboo or clay mixed with straw. The houses were built beautifully in every detail. Perhaps that was the reason they seemed so alive though they had been, in a sense, abandoned in 2002.

The houses at first seemed to be placed randomly, but they surrounded the communal house, nhà rông (literally, nhà, house and rông, being in an untied situation, like dogs roaming around). The nhà rông of Kon So Lal had been built, by the villagers, in 1978, with a thatched roof.

In the middle of the village were the refreshing green of mango trees and other fruits, vegetables and water-supply pipes of bamboo. The beauty was so primitive and original, particularly compared with what I had seen in many other villages in the Central Highlands.

There were a couple of pigs and goats and a roof, like an upside-down ‘V’, resting on the ground.

Mr Hyunh, the former head of the village, said that although he and his wife had moved to the new village several years earlier his family and others still visited the old place because they continued to farm nearby. A more important reason for Mr Hyunh to visit was that his father, about a hundred, was still living in old Kon So Lal, like four other village elders, Mr Chil, Mr Chung and Mr Koch and Mrs Dyoi, husband and wife. The latter four who were around seventy or eighty.

Mr Hyunh remembered that there had been 85 families, 454 people. The most cheerful and exciting times had been at harvest, when every house’s storage had been filled with new rice. The village boys and girls had gathered in the communal house. The boys had played gongs, the girls danced and the wine never finished. Now the festivals were all held in the new village, though the old village became less deserted when there was a funeral. Everyone wished to be buried in the old village.

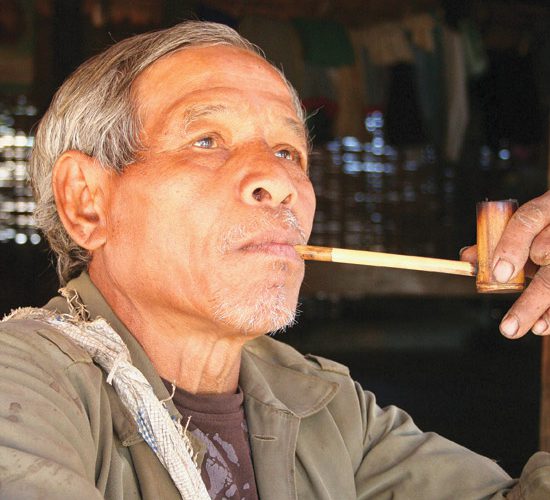

Mr Chil

Mr Chil, 67, who smoked a bamboo pipe, had six children who had all moved to the new village but he had not wanted to move. Sometimes, his children brought him rice and other food. When I asked why he chose to stay, he only smiled. I asked if he was bored, and he said, ‘When I’m bored I visit my children in the new village.’

My Hyunh’s father, Mr Hnhih, had lost a lot of his hearing. Sometimes his widowed daughter visited him and took him to the new village to see his grandchildren. He lit an oil lamp at the front of the house to weave bamboo baskets. Although his eyesight was poor and his hands shook, he could still make very beautiful baskets. In no time, he had made half of a basket from bamboo as thin as rice leaves, for his children.

When I was photographing the communal house in the new village, a group of boys playing football pointed in the direction of the old village and said, ‘You should photograph the communal house in the old village. It is much more beautiful.’

The new village of Kon So Lal was laid out like a chess board but next to every brick house was a stilt house. Mr Khok, vice-president of the Communist Party for the ward, told me many residents still preferred stilt houses, which suited their customs.

Mr Dinh Suk, president of the District People’s Committee, said that recently the rubber company Chu Pah had built a big road by Kon So Lal village, for collecting rubber, and, ‘If the road had been built earlier, people would not have had to leave their village.’

Once, I had had the opportunity to take part in a festival of the Bahnar in Kon Pne Ward, Kbang District, Gia Lai Province, Central Highlands, a ‘festival of planting’, one of the three largest of the Bahnar in that area. It had been in an old village, built in 1984, four kilometres from its new, ‘Stable-work, stable-life’ version. About half a kilometre from the old village I had felt the excitement in the air. I had heard the traditional musical instruments, gongs. I had seen the smoke coming out of the stilt houses’ kitchens.

Pigs, dogs and chickens had been running around. It had been as if the village had never been abandoned. The communal house had been full of people sitting around plenty of pots of wine.

I also recall that some years ago Nguyen Ngoc, a writer, and a film crew faced many difficulties in looking for locations in the Central Highlands. They were searching for a village like a traditional Bahnar one with no bricks and no tiled or metal roofs, rather stilts, bamboo and thatch. They spoke of boring villages versus ones with culture.

Stilt houses at the old

village of Kon So Lal, in March, 2011