(No.7, Vol.4,Aug-Sep 2014 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

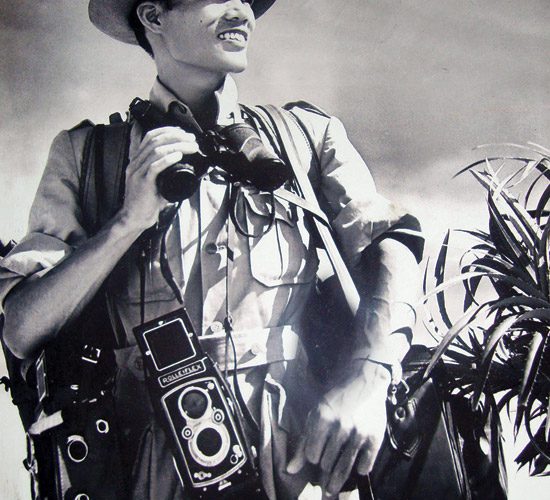

Photographer Nguyen Manh Dan at young age

Saigon’s most hardcore photographers consider him a ‘living archive’, ‘perennial tree’ of Vietnamese photographic art, the ‘king of landscape photography’, and a recorder of many historical events.

That respect urged me to spend a lot of effort to find his residence on Dien Bien Phu Street, in District 10 of Saigon.

Despite his age (89) and a stroke he suffered in 2012, he talked with great passion, enthusiasm and clarity about the art of photography when I touched on the topic.

Nguyen Manh Dan was born in 1925 in Nam Dinh, 100km from Hanoi. Growing up in a peasant family, he managed to study up to the middle school level. In 1945, he moved to Hanoi to work for a photo shop.

Puffing his cigarette deeply, the silver-hair-and-bearded old man recalls, ‘There were just a few photo shops in Hanoi at the time. Most of them used wooden cover cameras, and sulphur in a metal plate as flash. The photographer had to be quick to burn the sulphur and push the button at the same time.’

In 1948, robustly skilled and speaking French, he was hired by the French newspaper ‘Indochine Sud-Est Asiatique’ as a photographer. ‘I was working in the shop. A Frenchman walked in and asked for a photographer who spoke French. I stood up. The Frenchman looked at me from head to toe and said, ‘come to the editorial office tomorrow for probation.’ I was so stunned and happy. There were very few Vietnamese photographers working for the French at the time, so I was paid a lot of respect wherever I went.’

Since then, with a modern German Rolleiflex, Manh Dan scoured all the ins and outs of Hanoi and the Northern provinces. He was even present at some bloody battles between the French and the Viet Minh. Single-use magnesium flash was used at the time, so after frequent takes, his fingers were almost burnt changing the flash light. At nights he was back to the office to develop the film.

In 1950 the young talented news photographer was sent to Saigon. He was thrilled to discover the ‘Pearl of the Orient’ and Southern provinces.

By 1954, having gained recognition in the new land, he moved his family to Saigon. That was when he bought his first camera. In 1958, four years after the Americans replaced the French in the South, he quit his job.

After a decade as a news photographer, he was famous for many photographs published in French newspapers, including the famous Paris Match.

A French editor advised him to try to ‘capture the beauty of Vietnam’. To do that, he first opened Manh Dan photo shop to earn a living. ‘In Saigon, among the shops of those times, only my shop has survived until now,’ he asserted.

His fame lured customers to Manh Dan photo shop. After a few years, he had enough money to buy the latest equipment and a car. He started roaming around chasing visions. He was one of the first Vietnamese to practice artistic photography.

‘Sometimes I got a hunch at midnight and drove to Lam Dong, Nha Trang or Danang to take pictures,’ he related.

‘You were such an inspired soul,’ I exclaimed. The archive of life and profession just smiled brightly and philosophized, ‘Being free to create visions, without having to comply with petty requirements of the editorial office, my passion and skills soared. Each good picture made me immensely blissful.’

In 1975 the Americans withdrew. Vietnam was reunified and entered a period of economic meltdown. Facing financial difficulties like any other, Manh Dan the photographer never betrayed his passion. On every trip, he had to take with him food supplies and utensils to cook for himself.

In 1988, after 30 years of ‘capturing the beauty of Vietnam’, he decided to put down his camera.

‘40 years of practicing news and artistic photography, I have ploughed the whole country, from cities, mountains to islands far out in the sea, from Ban Gioc water fall the Northernmost to the Tho Chu Islands the Southernmost. And I have also toured the whole world.’

That’s how he took countless pictures; landscapes and portraits, war and peace.

‘Do you still have them?’ I asked. ‘When I worked for the news, I had to submit all, including the negatives. Later I was moving too much, partly because of war, and many were lost. Now I still keep some, but not much,’ he said.

From what was left, he published in five volumes: Vietnam in fire, 1969 (wartime pictures); Pictures of Vietnamese economy, 1974; Vietnam my native land, 1996; Scenes of Vietnam, 2003; and The land of the Viet, 2011.

Turning pages of his ‘The land of the Viet’, I saw many black and white lively images of long- gone nature and life: a corner in a pristine forest with big rough tree trunks, antique streets, peasants in palm leaf rain coats and old people with black lacquered teeth.

Photographer Manh Dan participated in many international exhibitions. He was a member of many associations such as VNPS, RPS, PSA, HOPA, and VAPA . . . and had been for a long time a member of the Art Committee of the Vietnam Association of Art Photography.

He won hundreds of international prizes. Between 1959 and 1963 he brought home over 70 medals. He has no domestic prize, ‘because I had always been a member of the jury, I was not allowed to submit my own works.’

The famous photographer Nguyen Cao Dam of the period 1950-1975 once remarked, ‘Nguyen Manh Dan is the king of landscape photography.’ Following some old sources, the international photographer community called him ‘Mr Pictorial.’

During 25 years since the time he stopped wandering and vision hunting, Manh Dan received numerous western guests, mostly French. ‘They think I have a lot of precious materials and come to ask for it.’

‘Has photography changed since then?’ I asked. ‘The pictures now are digital and much better processed. But they are not real. The feeling is not as real and deep as it used to be,’ he remarked.

After a deep silent contemplation, he said, ‘Perhaps the artist’s senses were sharper and stronger during the war, so they reached those depths, unattainable in the time of peace.’

Manh Dan has six sons and three daughters, and all have followed his footsteps. One of them, Mr Manh Sinh, is currently the Chair of the Art Committee of the Association of Art Photography of Ho Chi Minh City. Some of his grandchildren also have started following his trade.

‘What would you like to share with your descendants and today’s photographers?’ I hinted.

Taking a long deep puff with his third cigarette, the photographer-aestheticist said slowly, ‘In whatever genre you work, give it all you have, or you won’t have it at all. Don’t spend too much time and effort chasing fame, success and prizes. It will plane away your imagination. Once you have chosen a trade, pay your dues.’