(No.1, Vol.4, Jan-Feb 2014 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

I was born in 1947 in Hanoi, while it was occupied by the French. Tet always leaves the most vivid memories in children, because they have been waiting for it the whole year with all the excitement that only kids can have. The first sign of Tet was my mom selecting the best daffodil bulbs to plant for the New Year celebration. The daffodils are always the central piece of decoration in our family. All the other flowers are bought to be put in vases, but the daffodils are planted carefully, since they are just bulbs, black and rough like taros. Then, they are peeled and trimmed to make pearl-like white buds appear. Then, luxuriant green leaves and dense roots appear. Finally, the white flowers spring out with yellow stamen, refined and noble.

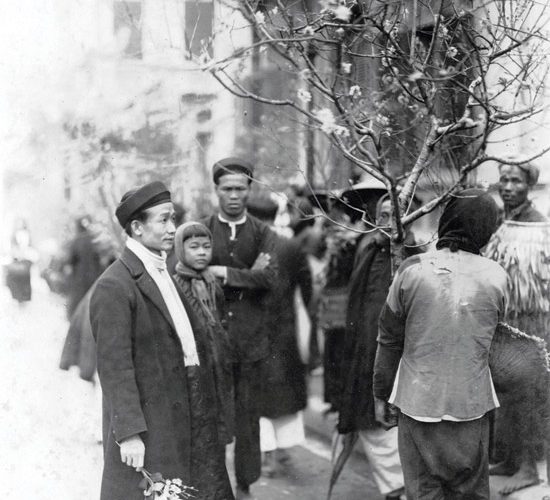

Tet in Hanoi in the 20th century. A photo from the L’Indochine Profonde by J.P. Dannaud. Photo provided by

Nguyen Anh Tuan.

My house was near the White Horse Temple on Hang Buom Street, the My Kinh restaurant and the Chinese restaurant Dong Hung Vien, all famous places. I used to see many daffodil pots on the temple’s altar. Later, I read in newspapers that Hanoi flower lovers used to organize a daffodil contest in Ngoc Son Temple on New Year’s Eve. Then, they had a procession to bring the winning pots to the White Horse Temple. Like all other temples, during Tet, a great many people come here to ask for good fortune, including Vietnamese and Chinese who live on Hang Buom and the neighbouring streets. Tradespeople also used to come here together to give pledges to smooth business relationships.

My family had a cloth shop on Hang Duong Street, which was a trading street near Dong Xuan, the biggest market of Hanoi. Near Tet, we had more customers. But this was the street of sweets. Cakes, candies, jams and salted fruits are the traditional merchandises for Tet. As for the Mid-Autumn Festival, sticky rice cake and sweet pies were favoured. It was said that it was the sweets piled up in Hang Duong for the New Year of 1947 that helped Hanoi defenders to hold out for two long months amidst the enemy’s siege.

My paternal grandma was the commander-in-chief of our little operation. She used to sit all day on the flat bed in the middle of the living room to give orders to family members and servants, to receive customers and guests from the countryside, to resolve financial matters and to shop and prepare for Tet.

We kids were responsible for tidying and cleaning the furniture in the living and the ancestral rooms. We felt both excited about Tet and displeased by having to meticulously clean every detail in the intricately carved wooden furniture with soft cloths so that everything would shine, be it bare or lacquered wood. Only the bronze ware was left to adults, because it required a special polishing substance.

Nearer to Tet, we kids begin to receive from our native village not clay pigs, but green bamboo cylinders with a slot to tuck in the lucky money, which we were allowed to ‘audit’ only after Tet. My paternal native site is Ben Tre, far down in the South, but my maternal site is just a short distance away. Every year, I accompanied my grandma there on a pedicab to visit the ancestral graves, the village temple and our relatives, near and far.

Our family did not need to make bánh ch?ng – the New Year rice cakes – but instead, took them from our nearby home village (Later, only when life became more difficult under the ration system, did we make them at home.) But a pot of green bean cake to offer to the altar and to eat during Tet was a must. These customs remain with us to this day. Plates of green bean cakes glowed with the golden colour of beans cooked on a low fire, finely stirred with a bamboo spoon. Sometimes, we went as far as to put it into a tightly-woven basket and rubbed it hard with a bowl to let the bean dough filter through the fine bamboo net. That way, the cake would melt cheeringly in the mouth with the savour of roasted sesame grains.

Hoan Kiem Lake, 1959. Photo: Dao Trinh.

Nowadays, people pour out to the streets around the Returned Sword Lake to greet the New Year. In those days, New Year’s Eve was the time for the family to gather at the ancestral altar. Only one person was charged to go out a short time before midnight, enough time to go to the nearest pagoda to offer some incense to heaven and earth and get home just after midnight to be the first person in the new year to set foot in the home to bring good fortune for the whole year. Then came the singing of water sellers, which symbolized a wish that money and good luck would come in like water that flows to hollow places. They would be tactful to knock only after the first foot setter.

In those days, although families were less dispersed than now, the gathering at New Year’s Eve was the most sacred feature of the holiday. It was the time for everybody to take turns to wish each other well-being in a strictly defined sequence. The lucky money was counted as a godsend, and everybody respectfully offered incense on the ancestral altar. Then, the offerings on the altar for heaven and earth, usually put on the porch or on the top floor, were taken down.

In those days, there was no Tet without firecrackers [now firecrackers are banned. Only fireworks are allowed on a limited scale]. Once they started bursting, hours before midnight, they continued long into the night. The loudest sounds came from Hang Buom Street. There was a grocery shop next to our house, owned by a Chinese, and someone kept knocking on door and asking for the firecrackers, even after midnight.

Later, I was told that the noise was from a firecracker competition between two big bosses, whose shops were opposite each other. Both burned small rolls of firecrackers long before midnight. The noise attracted on-lookers, so both wanted to boast having the longer roll, and neither wanted to stop first. They continuously joined their rolls together, hoping the other would give up first. The more people came to watch, the more zealous they became, and they sent their servants to buy out all the firecrackers in town to continue the contest.

Ngoc Son Temple, Hoan Kiem Lake, a popular place for people to visit during Tet. A photo from the L’Indochine Profonde by J.P. Dannaud. Photo provided by Nguyen Anh Tuan

The vying went on till late, although both sides ran out of firecrackers. Finally, they agreed to finish at the same time. Rumour had it that somebody told on them and the authorities had sent them a message, that at a certain time they had to stop the noise, or risk hefty fines for disturbing the public order.

At that time, firecrackers were made of red paper and bead tree charcoal was used as explosive, so the smell was soft and pleasant. The pinkish wrapping was torn and scattered evenly, like peach petals, announcing spring’s coming.

* Mr Duong Trung Quoc is a well-known historian based in Hanoi