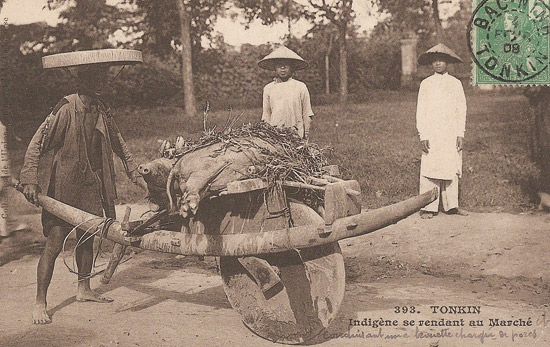

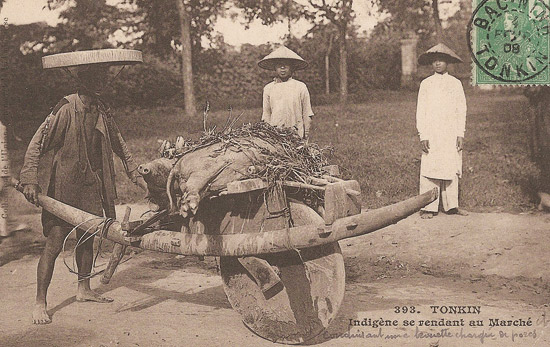

(No.6, Vol.4,Jul-Aug 2014 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

A single-wheeled handcart, near Hanoi, 1908

Photo from the archive of

collector Philippe Chaplain

The long, slow journey of the push cart

Prior to the twentieth-century, the means for conveying goods among the Vietnamese were quite primitive and belonged to the sorts of those societies most underdeveloped in the world at that time. In order to transport many things or those that were heavy, the sole form of transport was by boat. Indeed, the principle conveyance for construction rock along with major stones was for people to use rollers to carry them onto rafts and then take them to their destination via waterways. Trade on the waters by riverboat became a professional activity because so many rivers and streams crisscrossed the country and, from the rivers, people could make it to remote locations.

Transport over land by buffalo cart, oxcart, and horse cart was actually not that prevalent, since buffaloes and oxen were rather costly. Hence, shoulder poles and carrying goods on the head were a characteristic way of life. Vietnamese farmers could shoulder quite a load; thirty to forty kilograms was normal, while the heftier bore fifty to seventy. Shouldering water, paddy, firewood, and goods was an everyday activity, so nearly everyone could do it.

One of the most common transport means used was the single-wheeled handcart. It was the most ancient vehicle in the Orient; perhaps over two thousand years of age. They were quite primitive and included two long shafts attached at the front to a wheel made from the slice of a wooden log. The two shafts extended to the rear so that a person could hold them with both hands and push the cart forward. Goods were laden atop the two cart shafts.

Thus was the simplistic design of the pushcart, although, in the process of transporting goods along with people, it had been improved several times. With horse carts, the solid wheel was quite heavy and generated a great deal of friction, so the speed was not very high. Hence, people improved upon it by switching to a hollow wheel that included a circular rim and a central axle connected by spokes. Pushcarts, too, were thus improved. Nevertheless, in ancient Vietnamese villages, just making the spokes was rather difficult, so they used solid wheels all the way up until the twentieth century.

As the iron and steel industry developed, pushcarts made from iron also became prevalent on construction sites. The two shafts were attached to a barrow. At the head of the shafts was an iron wheel with spokes and a lubricated axle. Yet, this cart still screeched whenever the wheels turned, so it was chiefly referred to as the ‘squeaky-wheeled cart’ (xe cut kit).

In the book ‘Le Tonkin en 1900’ by R. Rubio (Paris, 1900), there are some photographs of Northern peasants transporting goods with the single-wheeled hand barrow. People set a bamboo floorboard on the two shafts so that the cart could be laden with a lot of goods, even two large barrels. Beneath the shafts, near the person pushing them, were two supporting legs. When at rest, the legs held the cart in place while keeping it standing. This hand barrow was also illustrated in the technology books of the Annamese and Henri Oger. The Chinese people, in their utilization of pushcarts, made an ingenious innovation. They affixed a pole and sail to the cart; if they went in the direction of the wind, the sail facilitated pushing the cart further and faster.

Many products such as the water-wheel, water mill, wheel, and turntable, are essentially considered the discoveries of agricultural societies. Nevertheless, whether imported from abroad or invented domestically, these products were seldom innovated and were applied multifariously, especially in the olden village communities of an agricultural form, where they endured for a long time.

The wooden solid-wheeled pushcart was a characteristic Vietnamese-fashioned product; despite humanity’s having switched to the spoked wheel all the way back in ancient Greece during the fifth to fourth centuries prior to the common era. Perhaps it retained the original features from the time when people [first] thought up this kind of cart all the way up until the nineteenth-century. Even after this cart disappeared from conventional farming life, its form remained unchanged.

The ball-bearing wheelbarrow was a second kind of product, which was a type of double-shafted handcart for either pushing or pulling. Later on, this handcart became prevalent in rustic villages during the war and was called the ‘innovated cart’ (xe cai tien). At first, it was just like the buffalo and horse carts, except that it was not pulled by domestic animals, but humans.

The business of running handcarts to pick up and drop off customers developed in Hanoi and Saigon during the French colonial period. In fact, it also developed throughout Asia, including China and India. Western gentlemen and dames as well as wealthy, important officials rented litters to travel in the mountains and forests, while they rented hand-pulled rickshaws in the cities — a story reflected in the writer Nguyen Cong Hoan’s ‘Horsemen and human horses’ (Nguoi ngua, ngua nguoi)*. As late as the 1970s, many labourers in Hanoi still employed themselves to pull handcarts for delivering goods. These hand-pulled carts were called ‘loading tricycles’ (xe ba gac). As for the hand-pulled rickshaws, they came to an end by the 1950s and were replaced by bicycle propelled rickshaws.

In the rural villages, the ‘loading tricycle’ was an important means of conveyance for firewood, paddy, straw, and even people who needed to go to the hospital. Later on, because the wooden wheels were too weighty and made getting around difficult, people improved upon it by installing gas tires and streamlining the vehicle. Women, too, could pull them, as they did during the war whilst the men all went into battle.

*‘Human horses’ was a derogatory term for rickshaw pullers and drivers

Hanoi, 1905. Photo from the archive of collector Philippe Chaplain

A handcart. Photo from the book ‘Le Tonkin en 1900’ (B?c K? N?m 1900), R.Dubois, published in Paris, 1900.

Photo provided by Nguyen Anh Tuan

A single-wheeled handcart. Photo from the book ‘Indochine profonde’,

J.P.Dannaud, 1954.

Photo provided by Nguyen Anh Tuan