No 3, Vol.5, April – May 2015

More than forty years later, I can still hear Senator McGovern’s words sailing into the frigid Washington afternoon from a podium none of us could see, as there were so many of us.

‘We are all prisoners of war,’ he said.

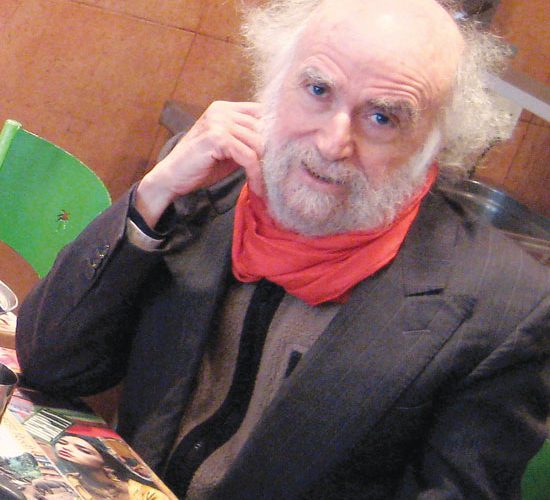

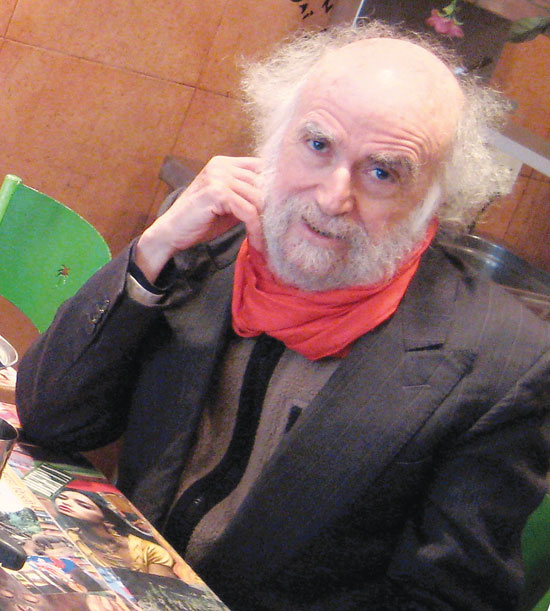

Robert Hirschfield

Philosophically among the truest words ever spoken by an American politician. The Vietnam War did imprison America. It built around itself a wall to keep sanity out. It incarcerated history in an airless room called the Domino Theory, for which three million Vietnamese and fifty-eight thousand Americans lost their lives. But the war did free those of us who opposed it from the prison of imagining war as an abstraction.

The faces of fleeing Vietnamese, of fearful Vietnamese, of dead and wounded Vietnamese, were our dinner companions (intruders, some might say) during the nightly news. We digested their images of suffering as we digested our food. For many years we ate the war in Vietnam without our being able to spit it out.

Every night, we would hear of the day’s ‘body count.’ As if the war was a factory and bodies were its inventory. I could not stop thinking about those ‘bodies.’ Who did they belong to? What kinds of lives were lived in those bodies? Lives that dreamt, grew bored, grew angry, told jokes, wrote poetry, had wives, had calluses?

A dangerous line of thinking. I knew others infected by it. It lead us into dark, disaffected, disruptive corners of ourselves, which in turn lead us (at least those of us who lived in Manhattan at the time) to Times Square one night, near the army recruitment office. We began by shouting the usual slogans that no one ever paid any attention to. Then we did something everyone paid attention to, especially ourselves, as such a thing had never been done before. We took out a Viet Cong flag and unfurled it under the shining lights of Broadway. We had crossed a forbidden border, and we all knew it. People rushed us from all sides grabbing at the flag, cursing us for waving it, for waving the flag of the enemy.

To feel like a stranger in your own country, hang out beneath the wrong flag in a time of war. Even an undeclared war. We walked around like characters in a Dostoyevsky novel, patrolling our unhappy underground, railing against a national mindset that could co-exist with napalm, Agent Orange, tiger cages, carpet bombings.

Unlike other Americans who opposed the war, and there of course were many who did, for us an essential connection had been broken between ourselves and the makers of American policy, between ourselves and the cold warriors in the media, like the Alsops, who wrote in support of that policy whose results could be seen every night on TV in the terrified eyes of villagers. The truth of the Vietnam War, unlike the wars we fought ever since, entered our living rooms and kitchens thanks to the reporters and their cameras. The intimacy of devastation.

The networks may have been on America’s side, but the cameras supported the Vietnamese. To see is to know. And to know is a burden. Some burdens can’t be put down. Some burdens break one down.

The Weathermen blew up buildings, robbed banks, killed policemen. Charlotte, my girl friend at the time (we were all in our twenties and thirties) committed suicide to protest the war. She was naturally disorganized, and the suicide note she sent to the Fifth Avenue Peace Parade Committee, was sent to the wrong address. No one who knew her was surprised.

I got into blood arguments with relatives. (Well, one or two maybe. An uncle here, a cousin there. My cousins, for the most part, lined up on the left. Our parents all went through the Great Depression. The America of the sixties and seventies was not the America of today.) I insisted on knowing how people could go through their lives as if nothing were happening. Had they no shame, no feeling? I was a prisoner of anger.

Even now, I still identify parts of this city with that time. When I am on the Upper West Side, around 94th or 95th Street, I think of Charlotte’s room in the run down Narragansett Hotel, where my girl friend would take out maps of Vietnam to show me where exactly a factory had been bombed, a school levelled. Her room was piled high with books about Vietnam, with articles from every major and minor magazine and newspaper dealing with Vietnam. She knew the names of low-level Viet Cong leaders. She spoke of the ‘DRV’ the way one speaks of family.

Being with her was like being in a Vietnamese room, with all its tears and mournful cries. I had never before known a person to grieve for a country. With Charlotte, you always knew that you were loved second best. She was not the girl friend you dream of, but it was she who introduced me to ‘Uncle Ho’s’ poetry, who told me how he’d mimic the gestures of Chou En Li behind his back. She was a one woman Vietnam search engine before the Internet.

Near my house on the Lower East Side is where the Catholic Workers set up to serve the poor. The radical priests, Dan and Phil Berrigan, came there to denounce the war. Daniel Ellsberg, author of the Pentagon Papers, spoke there with bitter regret of his one- time support for the war. Maybe one day someone will write a novel about Moratorium Day in Manhattan when secretaries went to work wearing black armbands to protest a war that had gone on far too long and with no good reason.

I sometimes wonder what became of those women. I sometimes wonder what became of my city, where people can now sleep so easily through our latest series of foreign wars. The war in Vietnam shook some of us awake. Some of us have never gone back to sleep.n