(No.2, Vol.3, Mar 2013 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

Travelling around Long Son Island, I saw many men with long hair tied up in buns and wearing traditional southern Vietnamese clothing, like people did one hundred years ago.

Phd Dinh Van Hanh of Vietnam Institue of Culture and Arts, Ho Chi Minh branch, says that there are few places where people still maintain as many of the old traits of southern culture as in Long Son. The island is in Ba Ria-Vung Tau Province, about 80 km to the northeast of Ho Chi Minh City.

Long Son Island has an area of 92 square kilometres and a population of 13,558 people, of which 65 to 70 percent are followers of Ong Tran religion (đạo ông Trần), Mr Vo Van Mui, the chairman of the People’s Committee of Long Son Commune said.

According to the Tourism Newsletter of Ba Ria Vung Tau Department of Culture, Sports and Tourism, published in the fourth quarter of 2012, the founder of Ong Tran religion was Le Van Muu, who was born in 1855, in Kien Giang, a province in the southwest region of Vietnam. He followed the Tứ Ân Hiếu Nghĩa (Four Debts of Gratitude) religion and participated in the French resistance. In 1900, to escape from the French pursuit, he and his 20 relatives sailed to Vung Tau, choosing Long Son Island, still uninhabited at the time, to settle. He and his men grew rice and harvested salt for living. He founded a religion based on the philosophy of Tứ Ân Hiếu Nghĩa.

Tứ Ân Hiếu Nghĩa was established by Ngo Loi in May, 1867, in An Giang Province; though being a Buddhist sect, its philosophy is the mixture of the teachings of Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism and the ancestor worshipping customs of Vietnamese people.

‘Mr Muu was often without any shirt on during the day, so the people called him “Mr Tran†(meaning Mr Upper Half-Naked) and he founded Mr Tran’s religion. With the philosophy that: “If you are a human being, your head must touch the sky, your feet must stamp on the ground,†he advised his followers to wear bà ba Ä‘en, the southern traditional black clothes, walk barefoot and wear their long hair in buns without any hats on their heads,’ said Hai Teo – a follower of Mr Tran’s religion.

He told the believers to worship God, fairies, Buddha, and saints; at the same time, he wrote poetry and read story books with themes of human decency to teach them about benevolence, propriety, loyalty, intellect, trustworthiness and filial piety.

His religion advocates no pagoda building, no prayer chanting, and no fasting or forcing followers to be vegetarians or to renounce family and dissolve love.

With such a ‘philosophy’ on eating, clothing and religious practices, the inhabitants on Long Son Island said that Mr Tran’s religion is simply an approach to being good people.

Documents from the People’s Committee of Long Son Commune show that Mr Tran also created distinctive customs, such as that on wedding ceremonies, only steamed sticky rice and tea should be offered on the ancestor altars, and there is no need to prepare any big feasts or select auspicious dates, as long as it is held on the 30, 1, 15 or 16 of lunar months . Also, the dead must be buried within 24 hours and the coffin can be recycled, because he believed that ‘in dying, everyone is equal’.

‘Many of the old traditions set by Mr Tran are still up kept by the people here,’ said Mr Mui. The religion is however non-existent elsewhere, says Dr Dinh Van Hanh.

After 10 years of residing in Long Son, Mr Tran appealed to believers for contribution to build some good houses made of rare wood. Some constructions are now still inside Nhà Lớn (the Big House) complex, which is recognized by Vietnamese government as a national historical and cultural relic.

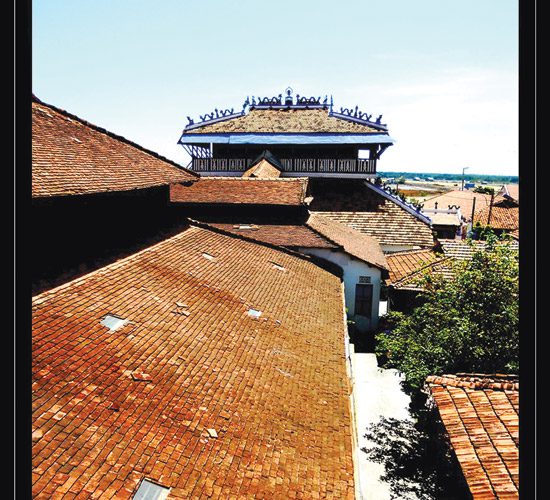

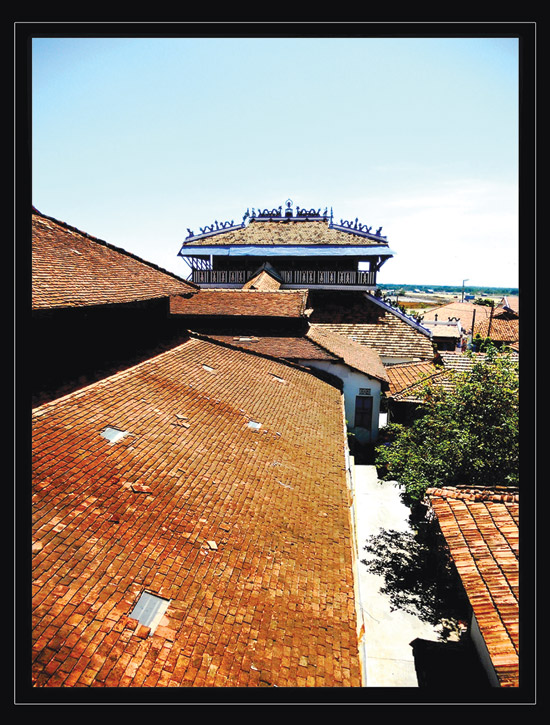

Nhà Lá»›n, the big house on Long Son Island, Ba Ria – Vung Tau Province

Photos: Le Thang My

The complex of Big House is divided into three sections, including: the worship section consisting of several houses joined together on nearly one hectare close to the foot of a hill (which is called Nua Mountain by the locals), the second section, about 5,000 square metres, is in front of the first section, including an exhibition house displaying a boat that Mr Tran used to travel to Long Son, an old market with three roof tile stalls left (now selling beverages for visitors), two rows of wood houses 50 metres in length, which were formerly used by passers-by and is now used as a free place for visitors to stay overnight, and the third section, an area of about 5,000 square metres, where Mr Tran’s tomb is surrounded by his family members’ and relatives’ ones.

The worship area has the architectural style of a Vietnamese village’s communal house with many interconnected or overlapped houses.

Right at the gate of the worship section is a spacious house where five older women wearing the southern traditional black clothes (bà ba) were sitting and making quid of betel. ‘We are making quid of betel to offer on his altar,’ one of them explained and reminded me: ‘You are only allowed to take pictures outside. No taking photos inside.’

I was whisked through my tour by a woman named Tu, and I felt lost, as if in a labyrinth.

Every house is mainly made of wood and has multiple columns. Each house has dozens of worship cabinets and furniture, which are carved very elaborately. It is said that Mr Tran collected a lot of tables, chairs, worship cabinets, horizontal lacquered boards and decorations for altars across the country.

After visiting the Big House, I was invited to a free vegetarian meal by Ms Tu with an explanation: ‘In the past, he often offered free meals for the poor and travellers who missed the path or rested for the night. Following his example, his descendants now also offer free meals for visitors in need.’

When I reached ‘the House of Rice Treat’, which has a capacity for more than 500 visitors, inside the worship section, I saw tens of huge stoves next to the kitchen area. An old woman named Nam, who was picking vegetables, said: ‘I often come here to cook for visitors as a charitable deed. Almost every follower of Ong Tran religion in Long Son Island has once come here to contribute their labour.’ She said: ‘On the maintenance, washing and cleaning only, more than 300 people take turns to do them and tens are in charge of working in the kitchen daily. On the two biggest festivals, which are his death anniversary on 20 February of Lunar Calendar (31 March this year) and Tet Trung Cuu (Double Nine Tet) on 9 September of Lunar Calendar (13 October, 2013) every year, there are thousands of people attending.’

Inside Nhà Lớn, the big house.

Long Son Island Commune belongs to Vung Tau city, Ba Ria – Vung Tau Province, 20 km to the southwest of Vung Tau city’s centre. There is a bridge connecting the National Road No. 51 to the island. From Ho Chi Minh City, follow the National Road No.1 about 25 km to the northeast, you will reach Vung Tau fork where you turn right into the National Road No. 51. Go about 56 km to reach Long Son fork at the milestone 56 km and 900 m; there you turn right again and go about 4.1 km to meet a fork and turn left to go straight on about 1.5 km, you will arrive at Long Son Big House (Nhà Lá»›n).

This section, covering Ba Ria – Vung Tau Province, is sponsored by Ba Ria – Vung Tau Department of Culture, Sports and Tourism.